Keith Kalani Akana

Title

Keith Kalani Akana

Subject

Nā Kumu Hula Keith Kalani Akana - Nānā I Nā Loea Hula Volume 2 Page 8

Description

Keith Kalani Akana

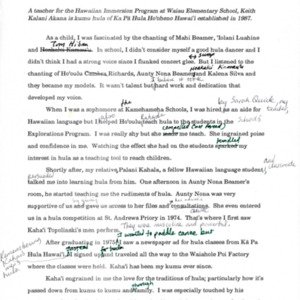

A teacher for the Hawaiian Immersion Program at Waiau Elementary School, Kalani Akana is kumu hula of Ka Pā Hula Hoʻoheno Hawaʻi established in 1987.

In school I didn’t consider myself a good hula dancer and I didn’t think I had a strong voice since I flunked concert glee. But I listened to the chanting of Ho‘oulu Richards, Nona Beamer. Hoakalei Kaniauʻu and Kalena Silva and they became my models. It wasn’t talent but I believe it took hard work and dedication that developed my voice.

When I was a sophomore at the Kamehameha Schools, I was hired by my teacher Sarah Quick as an aide for Hawaiian language but I also helped Hoʻoulu Richards teach hula to the students in the school’s Explorations Program. I was really shy but she compelled me to teach. She ingrained poise and confidence in me. Watching the effect she had on the students kindled my interest in hula as a teaching tool to reach children.

Shortly after, my relative Palani Kahala, a fellow Hawaiian language student and classmate, persuaded me to learn hula from him. One afternoon in Aunty Nona Beamer’s room, he started teaching me the rudiments of hula. Aunty Nona was very supportive of us by giving us access to her files and her advice. She even entered us in a hula competition at St. Andrews Priory in 1974.

That’s where I first saw Kahaʻi Topolinski’s men perform. They were masculine and powerful.

After graduating in 1975 I wanted to paddle canoe but I saw a newspaper ad for hula classes from Ka Pā Hula Hawaii. Remembering Kahaʻi’s men’s hula, I signed up and traveled all the way to the Waiāhole Poi Factory where the classes were held. Kahaʻi has been my kumu ever since.

Kahaʻi engrained in me the love for the traditions of hula; particularly how it’s passed down from kumu to kumu and through family. I was especially touched by his treatment of his family chants. I could see the direct tie between kumu, family, and the past. As a history buff he brings a great knowledge to each of his hula. He touched not only the emotional but the intellectual cord within me. He taught me how to discover my positive Hawaiian self.

I had what they call a huʻelepo ceremony. It was a private and small ceremony held at noon. It was attended by Kahaʻi, the family, and myself. We had those special ʻailolo foods, chanting, and pule. I observed a kapu period prior to the performance test and we had a small paʻina.

Kahaʻi was very gracious. He allowed me to take workshops from other people. I started taking chanting lessons from Kalena Silva and attended Aunty Edith Kanakaʻole’s workshops. Also I learned from Aunty Edith McKinzie whenever she conducted workshops for the State Council on Hawaiian Heritage.

I was fortunate to receive a scholarship at the University of Hawaiʻi in Hawaiian language from the Kamehameha Schools. I saw hula and chant as a vehicle to reach the Hawaiian youth but language is what tied it all together. I use this knowledge and my abilities in language to explain to the students the stories brought alive through the hula. Hula gave me an arena to internalize and ruminate on the meaning, kaona, and language.

I don’t like the term “hula kahiko.” We always used the word “hula ʻōlapa” in our hālau. Hula kahiko technically means “old hula” and I don’t like stereotyping hula as being something old. Our people had a name for every hula by its type and style: hula noho, hula ʻulīʻulī, hula palm, hula ʻālaʻapapa, and so on. A hula person must know all these kinds of hula. So hula kahiko is a broad term that is not linguistically correct and I think it’s too stifling because it doesn’t account for the traditional kinds of hula and for hula that we need to branch off into.

There are four important elements to become a successful kumu hula. First, language is the key for any aspiring kumu hula. Young people have an advantage because they can decide early on to learn the language. Secondly, whether they ʻūniki or not, they need a kumu or a mentor to turn to. That’s why we have the word kumu, meaning the source. If a person doesn’t have a kumu or a mentor, they’re going to flounder. Thirdly, a young kumu has to develop a style and creatively develop something unique that makes him/her a little different. And lastly, every kumu has to have and preserve the tradition of their hālau. If I teach a dance from my hālau, it’s my obligation to teach the exact way I learned the dance.

That my kumu is satisfied and approves of what I do is an accomplishment. Graduation is one way that the kumu acknowledges the student. Anyone can graduate if they put on a good show but the proof is if you can continue to please your kumu. If I didn’t do that, then there’s really no sense of me even continuing.

I have my masters, degree and soon I would like to start on my doctorate. But I can truthfully say, of all the formal Western style education that I’ve had, there’s greater satisfaction in the formal traditional graduation and training of hula. There’s a lot more pride, a lot more satisfaction. You receive much more than you can ever give. I’ve come to the realization that you cannot compare a degree with what you really get from the hula which is the pride of knowing that you are continuing a tradition.

“I saw hula and chant as a vehicle to reach the Hawaiian youth but language is what tied it all together. ”

A teacher for the Hawaiian Immersion Program at Waiau Elementary School, Kalani Akana is kumu hula of Ka Pā Hula Hoʻoheno Hawaʻi established in 1987.

In school I didn’t consider myself a good hula dancer and I didn’t think I had a strong voice since I flunked concert glee. But I listened to the chanting of Ho‘oulu Richards, Nona Beamer. Hoakalei Kaniauʻu and Kalena Silva and they became my models. It wasn’t talent but I believe it took hard work and dedication that developed my voice.

When I was a sophomore at the Kamehameha Schools, I was hired by my teacher Sarah Quick as an aide for Hawaiian language but I also helped Hoʻoulu Richards teach hula to the students in the school’s Explorations Program. I was really shy but she compelled me to teach. She ingrained poise and confidence in me. Watching the effect she had on the students kindled my interest in hula as a teaching tool to reach children.

Shortly after, my relative Palani Kahala, a fellow Hawaiian language student and classmate, persuaded me to learn hula from him. One afternoon in Aunty Nona Beamer’s room, he started teaching me the rudiments of hula. Aunty Nona was very supportive of us by giving us access to her files and her advice. She even entered us in a hula competition at St. Andrews Priory in 1974.

That’s where I first saw Kahaʻi Topolinski’s men perform. They were masculine and powerful.

After graduating in 1975 I wanted to paddle canoe but I saw a newspaper ad for hula classes from Ka Pā Hula Hawaii. Remembering Kahaʻi’s men’s hula, I signed up and traveled all the way to the Waiāhole Poi Factory where the classes were held. Kahaʻi has been my kumu ever since.

Kahaʻi engrained in me the love for the traditions of hula; particularly how it’s passed down from kumu to kumu and through family. I was especially touched by his treatment of his family chants. I could see the direct tie between kumu, family, and the past. As a history buff he brings a great knowledge to each of his hula. He touched not only the emotional but the intellectual cord within me. He taught me how to discover my positive Hawaiian self.

I had what they call a huʻelepo ceremony. It was a private and small ceremony held at noon. It was attended by Kahaʻi, the family, and myself. We had those special ʻailolo foods, chanting, and pule. I observed a kapu period prior to the performance test and we had a small paʻina.

Kahaʻi was very gracious. He allowed me to take workshops from other people. I started taking chanting lessons from Kalena Silva and attended Aunty Edith Kanakaʻole’s workshops. Also I learned from Aunty Edith McKinzie whenever she conducted workshops for the State Council on Hawaiian Heritage.

I was fortunate to receive a scholarship at the University of Hawaiʻi in Hawaiian language from the Kamehameha Schools. I saw hula and chant as a vehicle to reach the Hawaiian youth but language is what tied it all together. I use this knowledge and my abilities in language to explain to the students the stories brought alive through the hula. Hula gave me an arena to internalize and ruminate on the meaning, kaona, and language.

I don’t like the term “hula kahiko.” We always used the word “hula ʻōlapa” in our hālau. Hula kahiko technically means “old hula” and I don’t like stereotyping hula as being something old. Our people had a name for every hula by its type and style: hula noho, hula ʻulīʻulī, hula palm, hula ʻālaʻapapa, and so on. A hula person must know all these kinds of hula. So hula kahiko is a broad term that is not linguistically correct and I think it’s too stifling because it doesn’t account for the traditional kinds of hula and for hula that we need to branch off into.

There are four important elements to become a successful kumu hula. First, language is the key for any aspiring kumu hula. Young people have an advantage because they can decide early on to learn the language. Secondly, whether they ʻūniki or not, they need a kumu or a mentor to turn to. That’s why we have the word kumu, meaning the source. If a person doesn’t have a kumu or a mentor, they’re going to flounder. Thirdly, a young kumu has to develop a style and creatively develop something unique that makes him/her a little different. And lastly, every kumu has to have and preserve the tradition of their hālau. If I teach a dance from my hālau, it’s my obligation to teach the exact way I learned the dance.

That my kumu is satisfied and approves of what I do is an accomplishment. Graduation is one way that the kumu acknowledges the student. Anyone can graduate if they put on a good show but the proof is if you can continue to please your kumu. If I didn’t do that, then there’s really no sense of me even continuing.

I have my masters, degree and soon I would like to start on my doctorate. But I can truthfully say, of all the formal Western style education that I’ve had, there’s greater satisfaction in the formal traditional graduation and training of hula. There’s a lot more pride, a lot more satisfaction. You receive much more than you can ever give. I’ve come to the realization that you cannot compare a degree with what you really get from the hula which is the pride of knowing that you are continuing a tradition.

“I saw hula and chant as a vehicle to reach the Hawaiian youth but language is what tied it all together. ”

Citation

“Keith Kalani Akana,” Nā Kumu Hula Archive, accessed February 14, 2026, https://nakumuhula.org/archive/items/show/102.