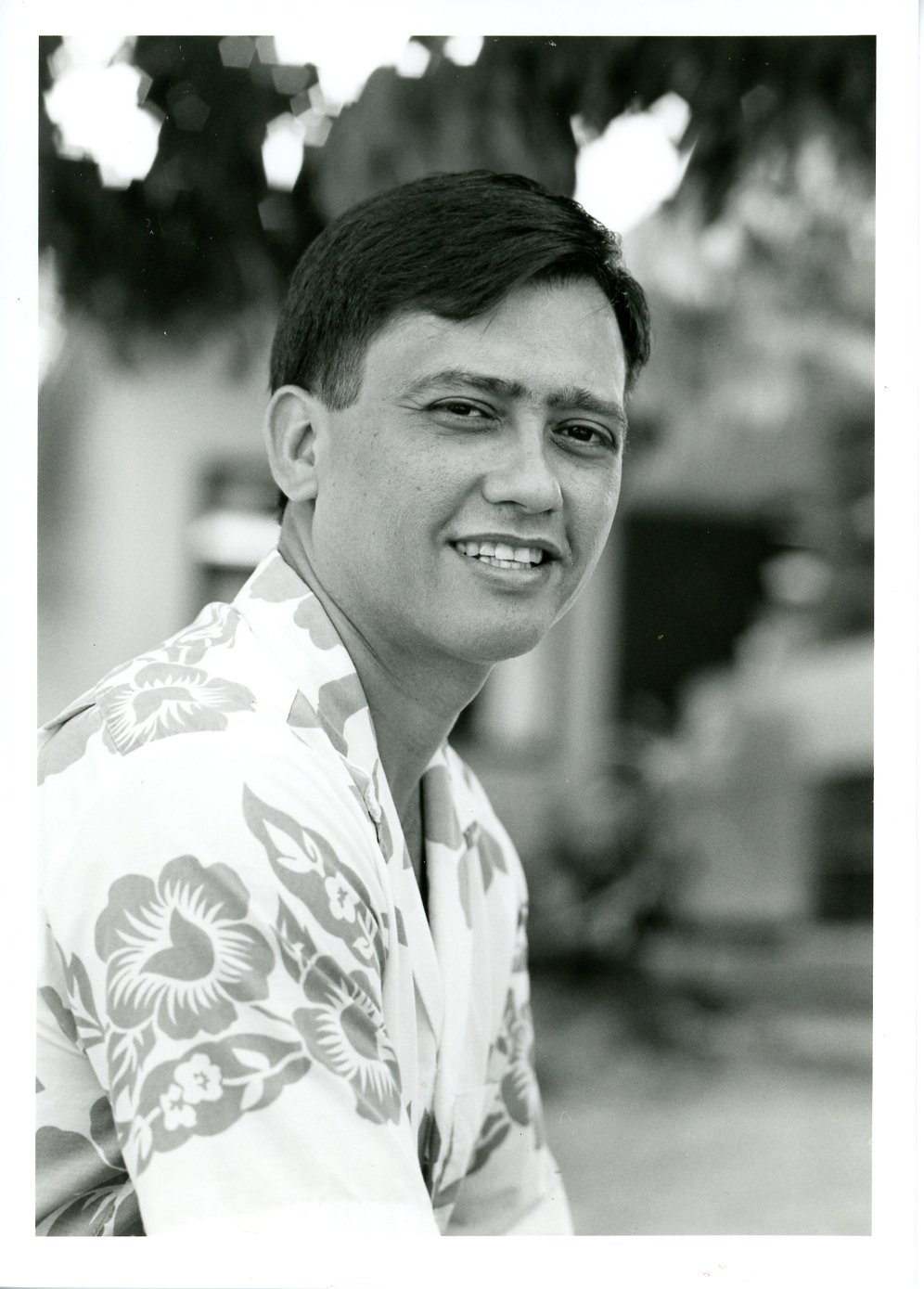

Nathan Napoka

Title

Nathan Napoka

Subject

Nā Kumu Hula Nathan Napoka - Nānā I Nā Loea Hula Volume 2 Page 87

Description

Nathan Napoka, currently employed by the State of Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources, has been teaching since 1975.

Hula has been in my family for generations. My great-great-grandmother was Ke'ele-hiwa Napoka, a famous court dancer from Maui who went to Kā'u to perform. Manuel Silva, a relative of my grandmother, learned from Ke‘elehiwa Napoka. My grandmother’s sister Elizabeth Kalehuawehe Chun Ling studied with Kumanaiwa who was a famous hula master on Maui. It is said that my family from that side of Maui performed what was called the Haleakalā dances which were done for Pele because she lived in Haleakalā up until very recent times. Everyone thinks of the Pele dances as coming from the big Island but there is a long tradition of Pele dances on Maui where she was still erupting in the 1700s. These dances were being performed until the 1900s.

I did not formally study hula until I returned to Hawaiʻi from college in 1972. At that time I was enrolled at the East-West Center as the Hawaiian Renaissance was just starting. Aunty Edith McKinzie was a student with me at the University of Hawaiʻi and she told me about the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts’ hula classes. Aunty Hoakalei Kamau‘u was the director of the program and Aunty Edith was teaching the beginning men’s class. After one semester with Aunty Edith, I moved into Aunty Hoakalei’s classes and I’ve been with her ever since.

I studied with Aunty Hoakalei with the understanding that she was going to prepare me to become a teacher. I was soon teaching all the beginning men’s classes for Aunty Hoakalei. I learned to be a ho‘opa‘a by chanting while sitting in the back of the advanced class. Aunty was in the front showing us how to dance and I followed. We also had a special class for the teachers to learn to oli.

I was coaxed into teaching. I was interested but I was afraid to teach. Through Aunty Hoakalei I learned that there is a whole way that you learn to become a teacher just like you learn to become a dancer or a chanter. For that reason I was very fortunate that she was (here to help me make a smooth transition from being a student to eventually running the class. She would come in and critique my teaching front the back and guide me through my classes. When she knew that I wasnʻt doing so well or when I was down emotionally, she’d come in and move me through the class. I had her guidance and her very strong presence to support me. That really gave me the confidence to teach: otherwise I would have never taught.

I later travelled throughout the state with Aunty ʻIolani Luahine and Aunty Hoakalei for about three and a half years with the Artist in the Schools program. I was very fortunate to have spent time with Aunty ‘Io. Aunty Hoakalei said only two men have ever danced professionally with Aunty ʻIo. I was one of the two. The other was Joseph Kahaulelio. There was a part of our program where I danced alone so that Aunty ʻIo could change clothes and then there was a part where Aunty ʻIo and I danced together. Although Aunty ʻIo wasn’t actually teaching me, we were doing the same motions because it was all coming from the same source. Aunty ʻIo was Aunty Hoakalei’s teacher.

Aunty Hoakalei doesn’t ʻūniki. Aunty Hoakalei didn’t ‘ūniki from Aunty ʻIo. ‘Ūniki is something for those people who are deep into the Hawaiian gods. In order to go through a formal graduation ceremony, you have to keep the gods in an altar. In order to keep the gods in an altar, you have to, what the Hawaiians say, “feed the gods" and that meant that you have to be a non-Christian. You cannot feed the Hawaiian gods today and forget about them tomorrow. If you dedicate your life to those gods, yon have to keep them for your whole life and not only when you want to dance hula. If you don’t keep them, they turn on you. Spiritually, they devour you.

‘Ūniki today is different than ‘ūniki yesterday. For people who are in traditional hula, a traditional ‘ūniki is nearly impossible because of the kapu system that existed when ‘ūniki was originally practiced. Today it has taken on a different meaning. Rather than the really strict traditional ceremony, it means a recital or a kind of graduation from one level to another. Like all healthy cultures, our culture is evolving.

My reason for dancing has always been to perpetuate these dances and to keep the culture alive. I’ve been very fortunate that my job has kept me financially secure so that I have never had to use my hula to make money. My hula has been something very special. It’s my identity; it’s my culture; it’s my expression.

Once in a while my work and hula have crossed paths. One such instance led me to Pat Bacon. Aunty Pat and I worked on indexing mele at the Bishop Museum for two years. During that time I was fortunate to learn more about ancient mele as well as my own hula background since Aunty Pat learned from Keahi Luahine, Aunty Hoakalei’s kupuna who was Aunty ‘Io’s hānai mother and teacher. Aunty Pat has generously given her time and brownies toward my development.

I think the hula has changed but I don’t think change is necessarily bad. The only thing that I see that’s bad is if we confuse our traditional hula with modern hula and if we don’t keep the classical hula and the contemporary hula separate. We have to safeguard what is traditional. To me hula kahiko is the classics; the motions and the voice that have been passed on from one generation to another, through one human being touching another human being.

If you ask most kumu hula today what they have in their repertoire that’s traditional, most of them don’t have much. They find the words in the archives and they make up the motions and the tune. Although it’s not bad, everyone should have some exposure to where they have come from as a people; where we have come as Hawaiians over all these millenniums of time.

Nānā I Nā Loea Hula 87

Hula has been in my family for generations. My great-great-grandmother was Ke'ele-hiwa Napoka, a famous court dancer from Maui who went to Kā'u to perform. Manuel Silva, a relative of my grandmother, learned from Ke‘elehiwa Napoka. My grandmother’s sister Elizabeth Kalehuawehe Chun Ling studied with Kumanaiwa who was a famous hula master on Maui. It is said that my family from that side of Maui performed what was called the Haleakalā dances which were done for Pele because she lived in Haleakalā up until very recent times. Everyone thinks of the Pele dances as coming from the big Island but there is a long tradition of Pele dances on Maui where she was still erupting in the 1700s. These dances were being performed until the 1900s.

I did not formally study hula until I returned to Hawaiʻi from college in 1972. At that time I was enrolled at the East-West Center as the Hawaiian Renaissance was just starting. Aunty Edith McKinzie was a student with me at the University of Hawaiʻi and she told me about the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts’ hula classes. Aunty Hoakalei Kamau‘u was the director of the program and Aunty Edith was teaching the beginning men’s class. After one semester with Aunty Edith, I moved into Aunty Hoakalei’s classes and I’ve been with her ever since.

I studied with Aunty Hoakalei with the understanding that she was going to prepare me to become a teacher. I was soon teaching all the beginning men’s classes for Aunty Hoakalei. I learned to be a ho‘opa‘a by chanting while sitting in the back of the advanced class. Aunty was in the front showing us how to dance and I followed. We also had a special class for the teachers to learn to oli.

I was coaxed into teaching. I was interested but I was afraid to teach. Through Aunty Hoakalei I learned that there is a whole way that you learn to become a teacher just like you learn to become a dancer or a chanter. For that reason I was very fortunate that she was (here to help me make a smooth transition from being a student to eventually running the class. She would come in and critique my teaching front the back and guide me through my classes. When she knew that I wasnʻt doing so well or when I was down emotionally, she’d come in and move me through the class. I had her guidance and her very strong presence to support me. That really gave me the confidence to teach: otherwise I would have never taught.

I later travelled throughout the state with Aunty ʻIolani Luahine and Aunty Hoakalei for about three and a half years with the Artist in the Schools program. I was very fortunate to have spent time with Aunty ‘Io. Aunty Hoakalei said only two men have ever danced professionally with Aunty ʻIo. I was one of the two. The other was Joseph Kahaulelio. There was a part of our program where I danced alone so that Aunty ʻIo could change clothes and then there was a part where Aunty ʻIo and I danced together. Although Aunty ʻIo wasn’t actually teaching me, we were doing the same motions because it was all coming from the same source. Aunty ʻIo was Aunty Hoakalei’s teacher.

Aunty Hoakalei doesn’t ʻūniki. Aunty Hoakalei didn’t ‘ūniki from Aunty ʻIo. ‘Ūniki is something for those people who are deep into the Hawaiian gods. In order to go through a formal graduation ceremony, you have to keep the gods in an altar. In order to keep the gods in an altar, you have to, what the Hawaiians say, “feed the gods" and that meant that you have to be a non-Christian. You cannot feed the Hawaiian gods today and forget about them tomorrow. If you dedicate your life to those gods, yon have to keep them for your whole life and not only when you want to dance hula. If you don’t keep them, they turn on you. Spiritually, they devour you.

‘Ūniki today is different than ‘ūniki yesterday. For people who are in traditional hula, a traditional ‘ūniki is nearly impossible because of the kapu system that existed when ‘ūniki was originally practiced. Today it has taken on a different meaning. Rather than the really strict traditional ceremony, it means a recital or a kind of graduation from one level to another. Like all healthy cultures, our culture is evolving.

My reason for dancing has always been to perpetuate these dances and to keep the culture alive. I’ve been very fortunate that my job has kept me financially secure so that I have never had to use my hula to make money. My hula has been something very special. It’s my identity; it’s my culture; it’s my expression.

Once in a while my work and hula have crossed paths. One such instance led me to Pat Bacon. Aunty Pat and I worked on indexing mele at the Bishop Museum for two years. During that time I was fortunate to learn more about ancient mele as well as my own hula background since Aunty Pat learned from Keahi Luahine, Aunty Hoakalei’s kupuna who was Aunty ‘Io’s hānai mother and teacher. Aunty Pat has generously given her time and brownies toward my development.

I think the hula has changed but I don’t think change is necessarily bad. The only thing that I see that’s bad is if we confuse our traditional hula with modern hula and if we don’t keep the classical hula and the contemporary hula separate. We have to safeguard what is traditional. To me hula kahiko is the classics; the motions and the voice that have been passed on from one generation to another, through one human being touching another human being.

If you ask most kumu hula today what they have in their repertoire that’s traditional, most of them don’t have much. They find the words in the archives and they make up the motions and the tune. Although it’s not bad, everyone should have some exposure to where they have come from as a people; where we have come as Hawaiians over all these millenniums of time.

Nānā I Nā Loea Hula 87

Citation

“Nathan Napoka,” Nā Kumu Hula Archive, accessed February 15, 2026, https://nakumuhula.org/archive/items/show/141.