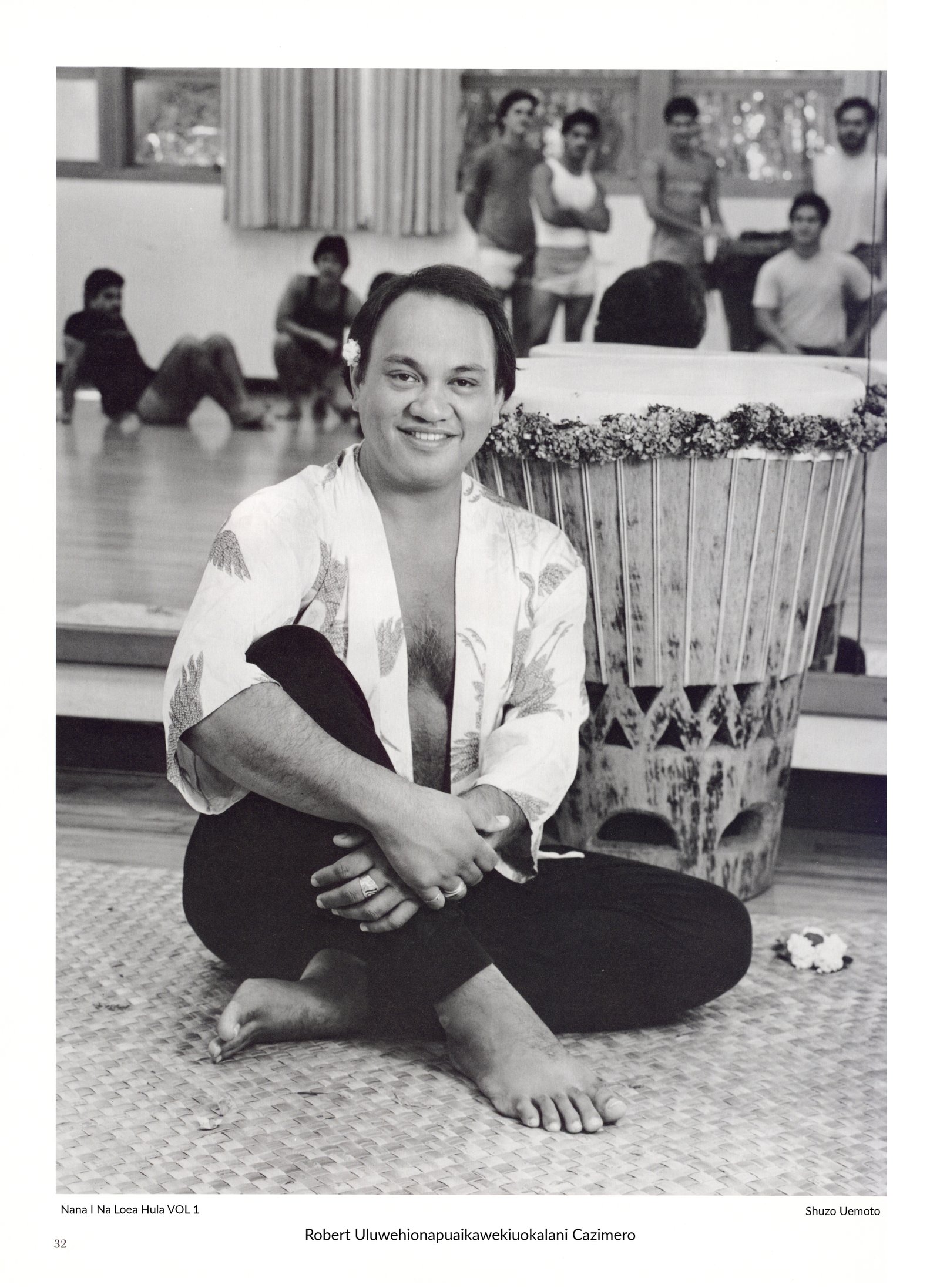

Robert Uluwehionapuāikawēkiuokalani Cazimero

Title

Robert Uluwehionapuāikawēkiuokalani Cazimero

Description

Robert Uluwehionapuāikawēkiuokalani Cazimero, widely regarded as a major influence in the rebirth of male hula in the 1970s, is kumu hula for Halau Na Kamalei.

In terms of the hula I feel I have shaken this state up. I have opened their eyes, I have kicked them in the pants but you know what? I didn’t even know I was doing it.

I was from a time in the Sixties where being Hawaiian was not important. It was more important to be American. You were trying to get through school so that you could work in Hawai‘i or maybe go away to school. The idea of hula was foreign. It was an embarrassment to want to do it for all of us. Men’s dancing was a novelty and I think to a point it still is today. Men just didn’t dance. Kaha‘i Topolinski started before me and I remember watching his boys and they were fabulous. Ed Collier was another one who had a male halau years before I even began to train. It took a lot of guts for a guy to get on stage back then. There was an immediate branding of being effeminate and so it was really hard. I’m glad that things have changed a little and I suppose on the surface it looks like it’s changed a lot but it really hasn’t.

Nona Beamer was my first kumu and she was my first contact with the hula. I was a sophomore at Kamehameha, guys were just beginning to dance and I was amazed. When Nona was teaching at Kamehameha there was a kapu on dancing. No one was allowed to stand up and dance and Nona changed all that. With Nona we began to stand up and actually dance. In my senior year Nona had us choose a song and interview the author. I had chosen Kui Lee and my dear friend Puna Kalama had chosen “Aloha Kaua‘i,” a song written by Ma‘iki Aiu Lake. Puna got her aunt to come to the class and I think I fell in love with her immediately. She sang for us and I accompanied her on the piano and when she left she told me to come to her if I ever wanted to learn hula.

It took me quite awhile to go to her but I started my training in 1968. The class was held one night a week, every Friday and we would go in and stay for several hours. When I think about it now it was like a dream. I was so taken with her that if she told me to jump off a building, willingly, with maile leis on, I would have gone. Classes were formal in the sense that you gave the respect to the teacher and you were there on time. She would start us off with having us sit in a circle and we would talk about what we had learned and what we would be learning. I was with Ma‘iki for seven years with the last five years training as a kumu hula. There are things that I did then that I regret now. If you talk to any of my hula brothers or sisters they’ll tell you that I was a spoiled brat. I was one of the favorites, I knew it, and I played it up. I was real cocky and I suppose I still am.

I graduated traditionally in 1972 and selfishly I felt at the time that I was ready to be a kumu hula. But now that I look back I didn’t possess the qualities needed. I taught informally in high school with my mother’s troupe and with the Sunday Manoa but it wasn’t until 1973 that I began to teach seriously. Ma‘iki had graduated me in 1973 as a ho‘opa‘a and ‘olapa, and in 1974 I was graduated as a kumu. There was an opening for a Hawaiian chant and dance instructor at Kamehameha and I applied for it. I taught three classes of girls which my kumu called my internship. Next was Na Kamalei which was formally founded on Kamehameha Day in 1975.

My definition of hula kahiko changes every year. Right now hula kahiko is anything that was taught to me before I became a teacher. Now that I am a teacher what I teach is a modern kind of kahiko. I consider myself a contemporary kumu and I like being a teacher of today. To me hula includes the sounds of jackhammers, cranes, buildings going up, traffic. I see hula in all of these things. The kumu of the past were not any different. They loved what they had but what they had is not what we have today.

The question to me is not what is kahiko but what is tasteful.

Of the twenty chants I learned from Ma‘iki, the boys have only been taught one. I guess I’m selfish. I won’t teach them, it’s too precious. It’s mine yet and when I’m ready to die or give things up then I’ll be ready to share it with them. I think the hardest thing that I had to come to terms with was the gossip and innuendo that was directed at my boys. People mistook my concern and love for my students as something more and I spent a long time trying to please public opinion. When I started in the hula one thing that I had made up my mind to do was prove that men could dance. That you didn’t have to just get up on stage and stomp around with a spear while hitting a paddle against a canoe. There is such a thing as manly grace. But it antagonized people and I became such a threat that everybody thought, well if he thinks he’s going to get away with that he’s crazy. It’s ironic how the young people of today with their own innovations have made my hula legitimate. Today they are doing things I would never have thought of or permitted myself to do. Yet 1 see myself in each of them.

In terms of the hula I feel I have shaken this state up. I have opened their eyes, I have kicked them in the pants but you know what? I didn’t even know I was doing it.

I was from a time in the Sixties where being Hawaiian was not important. It was more important to be American. You were trying to get through school so that you could work in Hawai‘i or maybe go away to school. The idea of hula was foreign. It was an embarrassment to want to do it for all of us. Men’s dancing was a novelty and I think to a point it still is today. Men just didn’t dance. Kaha‘i Topolinski started before me and I remember watching his boys and they were fabulous. Ed Collier was another one who had a male halau years before I even began to train. It took a lot of guts for a guy to get on stage back then. There was an immediate branding of being effeminate and so it was really hard. I’m glad that things have changed a little and I suppose on the surface it looks like it’s changed a lot but it really hasn’t.

Nona Beamer was my first kumu and she was my first contact with the hula. I was a sophomore at Kamehameha, guys were just beginning to dance and I was amazed. When Nona was teaching at Kamehameha there was a kapu on dancing. No one was allowed to stand up and dance and Nona changed all that. With Nona we began to stand up and actually dance. In my senior year Nona had us choose a song and interview the author. I had chosen Kui Lee and my dear friend Puna Kalama had chosen “Aloha Kaua‘i,” a song written by Ma‘iki Aiu Lake. Puna got her aunt to come to the class and I think I fell in love with her immediately. She sang for us and I accompanied her on the piano and when she left she told me to come to her if I ever wanted to learn hula.

It took me quite awhile to go to her but I started my training in 1968. The class was held one night a week, every Friday and we would go in and stay for several hours. When I think about it now it was like a dream. I was so taken with her that if she told me to jump off a building, willingly, with maile leis on, I would have gone. Classes were formal in the sense that you gave the respect to the teacher and you were there on time. She would start us off with having us sit in a circle and we would talk about what we had learned and what we would be learning. I was with Ma‘iki for seven years with the last five years training as a kumu hula. There are things that I did then that I regret now. If you talk to any of my hula brothers or sisters they’ll tell you that I was a spoiled brat. I was one of the favorites, I knew it, and I played it up. I was real cocky and I suppose I still am.

I graduated traditionally in 1972 and selfishly I felt at the time that I was ready to be a kumu hula. But now that I look back I didn’t possess the qualities needed. I taught informally in high school with my mother’s troupe and with the Sunday Manoa but it wasn’t until 1973 that I began to teach seriously. Ma‘iki had graduated me in 1973 as a ho‘opa‘a and ‘olapa, and in 1974 I was graduated as a kumu. There was an opening for a Hawaiian chant and dance instructor at Kamehameha and I applied for it. I taught three classes of girls which my kumu called my internship. Next was Na Kamalei which was formally founded on Kamehameha Day in 1975.

My definition of hula kahiko changes every year. Right now hula kahiko is anything that was taught to me before I became a teacher. Now that I am a teacher what I teach is a modern kind of kahiko. I consider myself a contemporary kumu and I like being a teacher of today. To me hula includes the sounds of jackhammers, cranes, buildings going up, traffic. I see hula in all of these things. The kumu of the past were not any different. They loved what they had but what they had is not what we have today.

The question to me is not what is kahiko but what is tasteful.

Of the twenty chants I learned from Ma‘iki, the boys have only been taught one. I guess I’m selfish. I won’t teach them, it’s too precious. It’s mine yet and when I’m ready to die or give things up then I’ll be ready to share it with them. I think the hardest thing that I had to come to terms with was the gossip and innuendo that was directed at my boys. People mistook my concern and love for my students as something more and I spent a long time trying to please public opinion. When I started in the hula one thing that I had made up my mind to do was prove that men could dance. That you didn’t have to just get up on stage and stomp around with a spear while hitting a paddle against a canoe. There is such a thing as manly grace. But it antagonized people and I became such a threat that everybody thought, well if he thinks he’s going to get away with that he’s crazy. It’s ironic how the young people of today with their own innovations have made my hula legitimate. Today they are doing things I would never have thought of or permitted myself to do. Yet 1 see myself in each of them.

Citation

“Robert Uluwehionapuāikawēkiuokalani Cazimero,” Nā Kumu Hula Archive, accessed June 29, 2025, https://nakumuhula.org/archive/items/show/23.