Mililani Allen

Title

Mililani Allen

Description

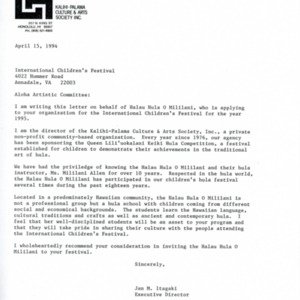

Mililani Allen began her teaching career in 1973 with the founding of Hālau Hula O Mililani in Waianae, 0‘ahu.

In the last ten years, the most significant change perpetuated upon the hula has been an increase of respect, scholarship, and interest. People have recognized it as a classical art expression of the Hawaiian culture. However, the style of dancing has changed because the greater emphasis today is on the dance itself rather than the language and poetry. I don’t look upon this as negative. There are so many of us that lack the fluency of the language and the understanding of the poetry. So the emphasis is now on the dance form rather than the verbiage of the mele. It is just another transition that has happened.

Exposed to hula at the age of six by my mother, I began my formal training under Aunty Mā‘iki Aiu Lake at the age of eleven. The lessons continued for three years until I entered high school and then they were interrupted by piano lessons then college. It was during my college years that my appreciation for the hula was nurtured and revitalized. Realizing my lack of knowledge in the art form contributed to my learning process and eventually it brought me back into the hālau after graduation from college.

I enrolled in Aunty Mā‘iki’s hula kahiko class and she emphasized the mechanics of the hula, the value of research, and written documentation of everything we learned. Her method to convey this knowledge of our culture was as much an oral presentation (“talk story”) as it was classroom-oriented. It was a positive reinforcement method and we were trained with succinctness.

Aunty Mā‘iki would first write the chants on a chalkboard and she would chant it for us. We were instructed to repeat the chant then allowed to write it in our notebooks. She was very positive in her approach. This was the most distinctive aspect of her teaching style and she remains a great influence on me today.

After my ‘ūniki with Aunty Mā‘iki, I studied with Aunty Edith Kanaka‘ole in workshops and Hawaiiana classes. Her teaching style was similar to Aunty Mā‘iki’s in that there was a tremendous giving atmosphere to Aunty Edith. It made me feel at ease and it allowed me the strength to give everything of myself. A lot of my style of dancing has been directly influenced by Aunty Edith so my hula kahiko is very simple. I’ve tried to keep in mind that the dancer is only the embellishment of the mele.

In 1973 I was now a wife and mother and my teaching career as a kumu hula became a reality. Before my sons were born I had been with the Department of Education, and hula teaching became the solution at the time to combine the continuation of my immersion into the Hawaiian culture and the raising of my children.

So far the reward and sacrifices have a way of balancing out. The formation of an ‘ohana demands sacrifice but it gives its own rewards. I think the most important service offered by my teaching has been the creation of a place for people, mostly women, to belong to apart from their daily routine and family. However, the privacy of my family is part of the sacrifice of being a kumu hula. The hālau members become part of your family and my time is shared with everyone. While this has been especially tough on my family, it has made my children stronger and better people.

The hula kahiko has changed but I think it is best to keep an open mind about these changes. My advice to my students is don’t put down someone because you think you know it all. You have to keep an open mind about people who want to study hula and about other members of other hālau. In the hula there are so many different styles of dancing, so many lines of knowledge, who’s to say what is right or wrong? We don’t know. I don’t think there was ever one right or wrong. In retrospect I don’t think there was ever one style of dancing in the hula. Hopefully, we will continue to develop many more.

In the last ten years, the most significant change perpetuated upon the hula has been an increase of respect, scholarship, and interest. People have recognized it as a classical art expression of the Hawaiian culture. However, the style of dancing has changed because the greater emphasis today is on the dance itself rather than the language and poetry. I don’t look upon this as negative. There are so many of us that lack the fluency of the language and the understanding of the poetry. So the emphasis is now on the dance form rather than the verbiage of the mele. It is just another transition that has happened.

Exposed to hula at the age of six by my mother, I began my formal training under Aunty Mā‘iki Aiu Lake at the age of eleven. The lessons continued for three years until I entered high school and then they were interrupted by piano lessons then college. It was during my college years that my appreciation for the hula was nurtured and revitalized. Realizing my lack of knowledge in the art form contributed to my learning process and eventually it brought me back into the hālau after graduation from college.

I enrolled in Aunty Mā‘iki’s hula kahiko class and she emphasized the mechanics of the hula, the value of research, and written documentation of everything we learned. Her method to convey this knowledge of our culture was as much an oral presentation (“talk story”) as it was classroom-oriented. It was a positive reinforcement method and we were trained with succinctness.

Aunty Mā‘iki would first write the chants on a chalkboard and she would chant it for us. We were instructed to repeat the chant then allowed to write it in our notebooks. She was very positive in her approach. This was the most distinctive aspect of her teaching style and she remains a great influence on me today.

After my ‘ūniki with Aunty Mā‘iki, I studied with Aunty Edith Kanaka‘ole in workshops and Hawaiiana classes. Her teaching style was similar to Aunty Mā‘iki’s in that there was a tremendous giving atmosphere to Aunty Edith. It made me feel at ease and it allowed me the strength to give everything of myself. A lot of my style of dancing has been directly influenced by Aunty Edith so my hula kahiko is very simple. I’ve tried to keep in mind that the dancer is only the embellishment of the mele.

In 1973 I was now a wife and mother and my teaching career as a kumu hula became a reality. Before my sons were born I had been with the Department of Education, and hula teaching became the solution at the time to combine the continuation of my immersion into the Hawaiian culture and the raising of my children.

So far the reward and sacrifices have a way of balancing out. The formation of an ‘ohana demands sacrifice but it gives its own rewards. I think the most important service offered by my teaching has been the creation of a place for people, mostly women, to belong to apart from their daily routine and family. However, the privacy of my family is part of the sacrifice of being a kumu hula. The hālau members become part of your family and my time is shared with everyone. While this has been especially tough on my family, it has made my children stronger and better people.

The hula kahiko has changed but I think it is best to keep an open mind about these changes. My advice to my students is don’t put down someone because you think you know it all. You have to keep an open mind about people who want to study hula and about other members of other hālau. In the hula there are so many different styles of dancing, so many lines of knowledge, who’s to say what is right or wrong? We don’t know. I don’t think there was ever one right or wrong. In retrospect I don’t think there was ever one style of dancing in the hula. Hopefully, we will continue to develop many more.

Citation

“Mililani Allen,” Nā Kumu Hula Archive, accessed February 21, 2026, https://nakumuhula.org/archive/items/show/29.