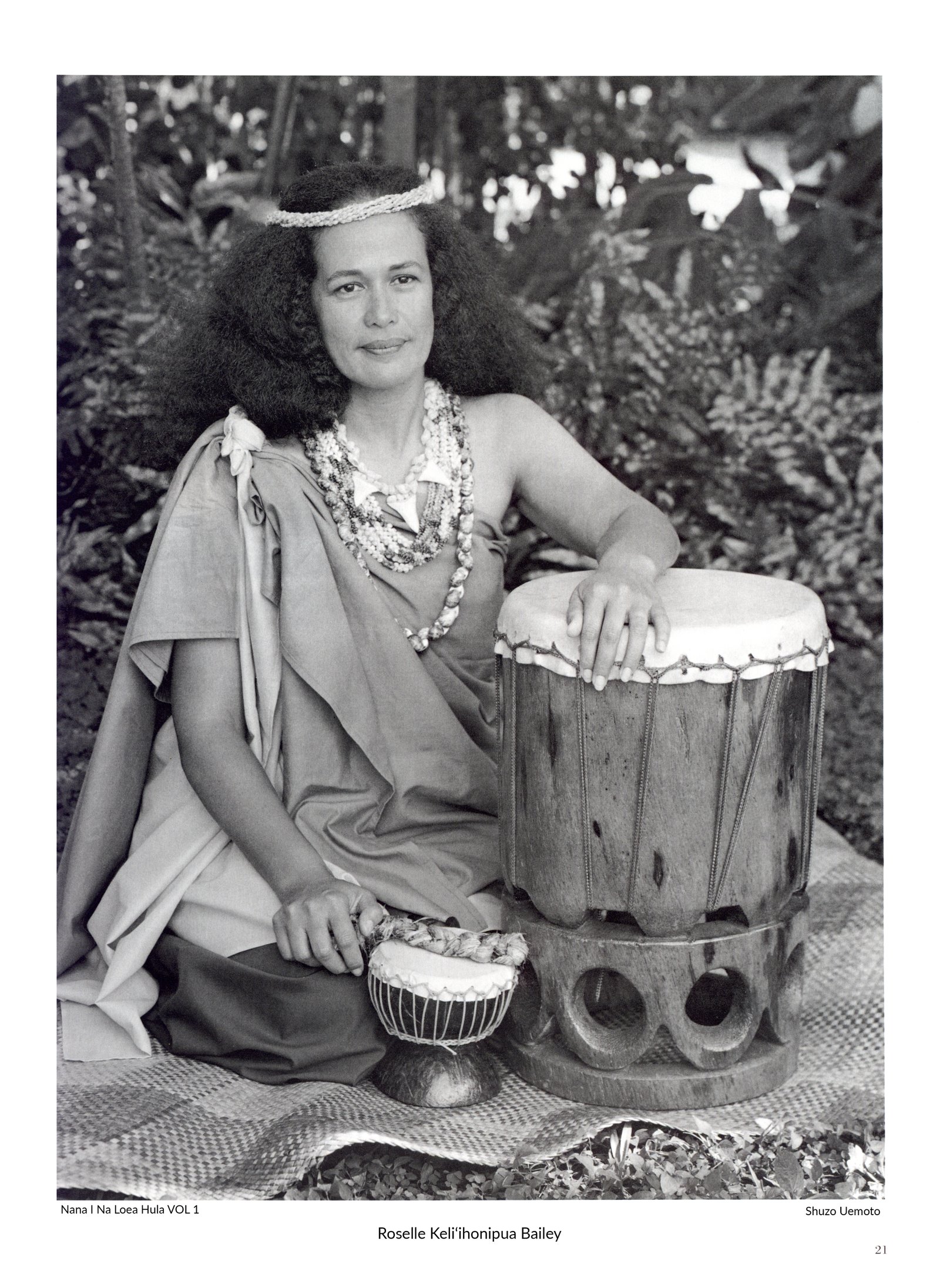

Roselle Keli‘ihonipua Bailey

Title

Roselle Keli‘ihonipua Bailey

Description

Roselle Keli‘ihonipua Bailey

Roselle Bailey is the founder of the hula hālau Ka‘Imi Na‘auao O Hawaii Nei and currently makes her home in Kaumakani, Kaua‘i.

In 1971 I had just come back from living abroad. I was literally more Arab than Hawaiian. From head to toe I was really a foreigner, from my clothes, to my speech, to my gestures. While living in Iraq I would have dreams of home. I would dream of Hawaiian words and phrases half a world away. When I came home Aunty Edith Kanaka‘ole was the only one that said she would help me. When I got together with Aunty Edith, it was like coming back to my roots. I would go once a week to her home for chanting lessons. The lessons included much more than chanting. We did a lot of talking about ‘ohana, giving openly and not holding anything back. For that I give Aunty Edith a lot of credit. She had that kind of soul thinking and feeling.

My first kumu was Aunty Emma Sharpe. When a person is four-years-old, he or she is never interested in the hula as a profession. I was just told to dance. From four years old to the fourth grade I thought of nothing but to be a good child and follow directions.

Later, I started to teach my own peers in high school but I’ve never considered myself a kumu hula although others have called me that. To me an ‘ūniki means that you have graduated in the traditional ceremonies and you are qualified to go on to teach. I’ve never gone through a traditional ‘ūniki. I think the qualifications for a kumu are tremendous because you not only have to know the motions of the hula but you have to be able to interpret a mele, visually and vocally. A true kumu has to be a psychologist, psychoanalyst, historian, naturalist, priest, choreographer, nurse, sister, and mother.

Today I base a great amount of my work upon the background of the twenty lessons that I received from Aunty Kau‘i Zuttermeister in 1974-75. It was what Aunty Edith taught me in 1971 that helped me understand and appreciate what Aunty Kau‘i stressed in 1974.

Aunty Emma set my foundation and my chanting style in a combination of Aunty Edith and Aunty Kau‘i but it is my parents that I consider my keepers. My mother trained under Aunty Emma and Lydia Kekuewa, and my father trained under his great-granduncle whom we call Tūtū Lama. These people helped set the foundation for our hālau which has been in existence for over ten years.

Today you have many more people in the hula so you have a lot of outside influences. I see ballet, modern dance and martial arts movements being used in the hula. Every mele dictates a certain kind of hula and certain styles of drumming belong to certain instruments as opposed to another. You shouldn’t put an ipu beat on a pahu but it’s being done today. I think there has to be an awareness of two categories within the kahiko being performed today. There is the hula kahiko that has been handed down from generation to generation that is a classical dance. Then there is a hula kahiko composed today in the style of the traditional hula. It is this contemporary kahiko that we are seeing the most of today.

The hula offers the modern Hawaiian of today a sense of identification. I feel that is most important. It is something from their culture that they can actually see that has been done for eons and they can say that’s a part of me. That’s the reason why we have to keep the traditional hula within it’s own realm or something is going to be lost from this record of our past.

Roselle Bailey is the founder of the hula hālau Ka‘Imi Na‘auao O Hawaii Nei and currently makes her home in Kaumakani, Kaua‘i.

In 1971 I had just come back from living abroad. I was literally more Arab than Hawaiian. From head to toe I was really a foreigner, from my clothes, to my speech, to my gestures. While living in Iraq I would have dreams of home. I would dream of Hawaiian words and phrases half a world away. When I came home Aunty Edith Kanaka‘ole was the only one that said she would help me. When I got together with Aunty Edith, it was like coming back to my roots. I would go once a week to her home for chanting lessons. The lessons included much more than chanting. We did a lot of talking about ‘ohana, giving openly and not holding anything back. For that I give Aunty Edith a lot of credit. She had that kind of soul thinking and feeling.

My first kumu was Aunty Emma Sharpe. When a person is four-years-old, he or she is never interested in the hula as a profession. I was just told to dance. From four years old to the fourth grade I thought of nothing but to be a good child and follow directions.

Later, I started to teach my own peers in high school but I’ve never considered myself a kumu hula although others have called me that. To me an ‘ūniki means that you have graduated in the traditional ceremonies and you are qualified to go on to teach. I’ve never gone through a traditional ‘ūniki. I think the qualifications for a kumu are tremendous because you not only have to know the motions of the hula but you have to be able to interpret a mele, visually and vocally. A true kumu has to be a psychologist, psychoanalyst, historian, naturalist, priest, choreographer, nurse, sister, and mother.

Today I base a great amount of my work upon the background of the twenty lessons that I received from Aunty Kau‘i Zuttermeister in 1974-75. It was what Aunty Edith taught me in 1971 that helped me understand and appreciate what Aunty Kau‘i stressed in 1974.

Aunty Emma set my foundation and my chanting style in a combination of Aunty Edith and Aunty Kau‘i but it is my parents that I consider my keepers. My mother trained under Aunty Emma and Lydia Kekuewa, and my father trained under his great-granduncle whom we call Tūtū Lama. These people helped set the foundation for our hālau which has been in existence for over ten years.

Today you have many more people in the hula so you have a lot of outside influences. I see ballet, modern dance and martial arts movements being used in the hula. Every mele dictates a certain kind of hula and certain styles of drumming belong to certain instruments as opposed to another. You shouldn’t put an ipu beat on a pahu but it’s being done today. I think there has to be an awareness of two categories within the kahiko being performed today. There is the hula kahiko that has been handed down from generation to generation that is a classical dance. Then there is a hula kahiko composed today in the style of the traditional hula. It is this contemporary kahiko that we are seeing the most of today.

The hula offers the modern Hawaiian of today a sense of identification. I feel that is most important. It is something from their culture that they can actually see that has been done for eons and they can say that’s a part of me. That’s the reason why we have to keep the traditional hula within it’s own realm or something is going to be lost from this record of our past.

Citation

“Roselle Keli‘ihonipua Bailey,” Nā Kumu Hula Archive, accessed August 25, 2025, https://nakumuhula.org/archive/items/show/32.