Ho'oulu Cambra

Title

Ho'oulu Cambra

Description

Ho‘oulu Cambra

Ho‘oulu Cambra is a member of the faculty of the University of Hawaii at Mānoa and the Kamehameha Schools.

If a person has Hawaiian blood, one might presume this precludes an inherent awareness, an affinity to the culture from within enabling one to catch on to the knowledge of the hula and the chants faster than a non-Hawaiian because this is the history of the race, this is the individual’s past.

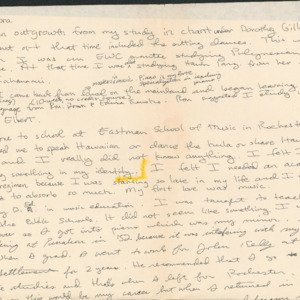

My life in the hula has really been an outgrowth from my training in music, Hawaiian language, and chant. In 1956 I attended the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York. My first love is music and I was taught to teach it in the public schools but I began to realize that it wasn’t something that I wanted to do forever.

When I returned from the Mainland in 1958, I taught piano at the Punahou Music School to make ends meet but I became restless so I took up ethnomusicology at the University which is a more scientific approach to the music of the world. My interest at that time was in the Hawaiian language and between 1958 and 1964 I studied under Rob Brown, Edwina Kanoho, Dr. Samuel Elbert, Kalani Meinecke, and Dorothy Kahananui. In 1962 I was introduced to Dorothy Gillett, the daughter of Dorothy Kahananui, and it was Mrs. Gillett who got me excited about traditional Hawaiian chanting. I was an East-West Center grantee studying Polynesian dance and music at the time, and from Mrs. Gillett I was led to Ka‘upena Wong who took me even deeper into the knowledge and traditions of chant.

The next logical step from the chant was to be trained in the dance. In 1971 I met Aunty Mā‘iki Aiu Lake and she has been my greatest influence because she taught me the intricacies of teaching the hula. She gave me a methodology and a set of goals to guide myself. I went to Aunty Mā‘iki because I felt I needed an academic, university-style regimen since I was starting my training so late in life. I needed to absorb so much, so I needed a hālau with a strong structure. I had studied at the University under Hoakalei KamauTi in 1965 — 66 but Aunty Ma‘iki was the first regimented academic situation I had in the hula. Ma‘iki’s class was a school in that it had a curriculum and expectations. There were examinations to be passed and assignments to be completed.

I graduated as the first kumu hula of Hālau Hula O Māʻiki in August of 1972 in a traditional ‘ūniki. In 1975 I went on to train under Aunty Kau‘i Zuttermeister for six months. There I was taught to chant in the Pua Ha‘aheo style and I found the discipline and regimentation of Aunty Kau‘i’s hālau similar to Aunty Māʻiki’s school. Some of my kumu have had a greater influence on me than others but I am grateful to all of them because they were all there to share with me at a time when I was hungry for their knowledge.

I began to give individual instruction in traditional chant for beginners in 1967 at the Music Department of the University with the approval of Dorothy Gillett, Kaʻupena Wong, and Hoakalei Kamauu and that was the start of my teaching career. I regard the hula as an art, specifically a living art that must be worked at and prepared for constantly. This is a very slow, tedious process that requires many procedures because I insist that my students study the history and culture relevant to the particular dance and chant they are learning.

It has always amazed me how the composers of these chants were able to combine major ideas and themes into a few, concise, terse lines. You can’t help but respect and admire the Hawaiian culture if you know the language and can read the chants. Hula is a way of life, it is a people’s inspiration. It is the Hawaiian’s connection to the universe around him. That is why books and pencils have very little place in this type of school. The dilemma is of course that without paper and pencil today’s students would have great difficulty retaining what I have to pass down to them.

My kumu taught me that contemporary chants and hula written in the kahiko style cannot be considered traditional. It must be handed down from generation to generation in its entirety. Kahiko is a convenient term used more to define what is not modern hula rather than what is traditional hula. I don’t know if students are learning the vast vocabulary of the hula and the chants that are essential to its perpetuation. Our young people are very impatient and very eager for the finished product. Audiences of today seem to goad the dancer into dancing more suggestively. The more exaggerated the dancer’s ‘ami, the more it satisfies the audience.

The modern audience is attracted mainly to the graphics of the dance. Their reaction to the hula ma‘i at times is to hoot and yell. These are products of the American culture where talk of sex is suppressed and thus when they see hula ma‘i, it’s their chance to react freely.

Ho‘oulu Cambra is a member of the faculty of the University of Hawaii at Mānoa and the Kamehameha Schools.

If a person has Hawaiian blood, one might presume this precludes an inherent awareness, an affinity to the culture from within enabling one to catch on to the knowledge of the hula and the chants faster than a non-Hawaiian because this is the history of the race, this is the individual’s past.

My life in the hula has really been an outgrowth from my training in music, Hawaiian language, and chant. In 1956 I attended the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York. My first love is music and I was taught to teach it in the public schools but I began to realize that it wasn’t something that I wanted to do forever.

When I returned from the Mainland in 1958, I taught piano at the Punahou Music School to make ends meet but I became restless so I took up ethnomusicology at the University which is a more scientific approach to the music of the world. My interest at that time was in the Hawaiian language and between 1958 and 1964 I studied under Rob Brown, Edwina Kanoho, Dr. Samuel Elbert, Kalani Meinecke, and Dorothy Kahananui. In 1962 I was introduced to Dorothy Gillett, the daughter of Dorothy Kahananui, and it was Mrs. Gillett who got me excited about traditional Hawaiian chanting. I was an East-West Center grantee studying Polynesian dance and music at the time, and from Mrs. Gillett I was led to Ka‘upena Wong who took me even deeper into the knowledge and traditions of chant.

The next logical step from the chant was to be trained in the dance. In 1971 I met Aunty Mā‘iki Aiu Lake and she has been my greatest influence because she taught me the intricacies of teaching the hula. She gave me a methodology and a set of goals to guide myself. I went to Aunty Mā‘iki because I felt I needed an academic, university-style regimen since I was starting my training so late in life. I needed to absorb so much, so I needed a hālau with a strong structure. I had studied at the University under Hoakalei KamauTi in 1965 — 66 but Aunty Ma‘iki was the first regimented academic situation I had in the hula. Ma‘iki’s class was a school in that it had a curriculum and expectations. There were examinations to be passed and assignments to be completed.

I graduated as the first kumu hula of Hālau Hula O Māʻiki in August of 1972 in a traditional ‘ūniki. In 1975 I went on to train under Aunty Kau‘i Zuttermeister for six months. There I was taught to chant in the Pua Ha‘aheo style and I found the discipline and regimentation of Aunty Kau‘i’s hālau similar to Aunty Māʻiki’s school. Some of my kumu have had a greater influence on me than others but I am grateful to all of them because they were all there to share with me at a time when I was hungry for their knowledge.

I began to give individual instruction in traditional chant for beginners in 1967 at the Music Department of the University with the approval of Dorothy Gillett, Kaʻupena Wong, and Hoakalei Kamauu and that was the start of my teaching career. I regard the hula as an art, specifically a living art that must be worked at and prepared for constantly. This is a very slow, tedious process that requires many procedures because I insist that my students study the history and culture relevant to the particular dance and chant they are learning.

It has always amazed me how the composers of these chants were able to combine major ideas and themes into a few, concise, terse lines. You can’t help but respect and admire the Hawaiian culture if you know the language and can read the chants. Hula is a way of life, it is a people’s inspiration. It is the Hawaiian’s connection to the universe around him. That is why books and pencils have very little place in this type of school. The dilemma is of course that without paper and pencil today’s students would have great difficulty retaining what I have to pass down to them.

My kumu taught me that contemporary chants and hula written in the kahiko style cannot be considered traditional. It must be handed down from generation to generation in its entirety. Kahiko is a convenient term used more to define what is not modern hula rather than what is traditional hula. I don’t know if students are learning the vast vocabulary of the hula and the chants that are essential to its perpetuation. Our young people are very impatient and very eager for the finished product. Audiences of today seem to goad the dancer into dancing more suggestively. The more exaggerated the dancer’s ‘ami, the more it satisfies the audience.

The modern audience is attracted mainly to the graphics of the dance. Their reaction to the hula ma‘i at times is to hoot and yell. These are products of the American culture where talk of sex is suppressed and thus when they see hula ma‘i, it’s their chance to react freely.

Citation

“Ho'oulu Cambra,” Nā Kumu Hula Archive, accessed February 13, 2026, https://nakumuhula.org/archive/items/show/37.