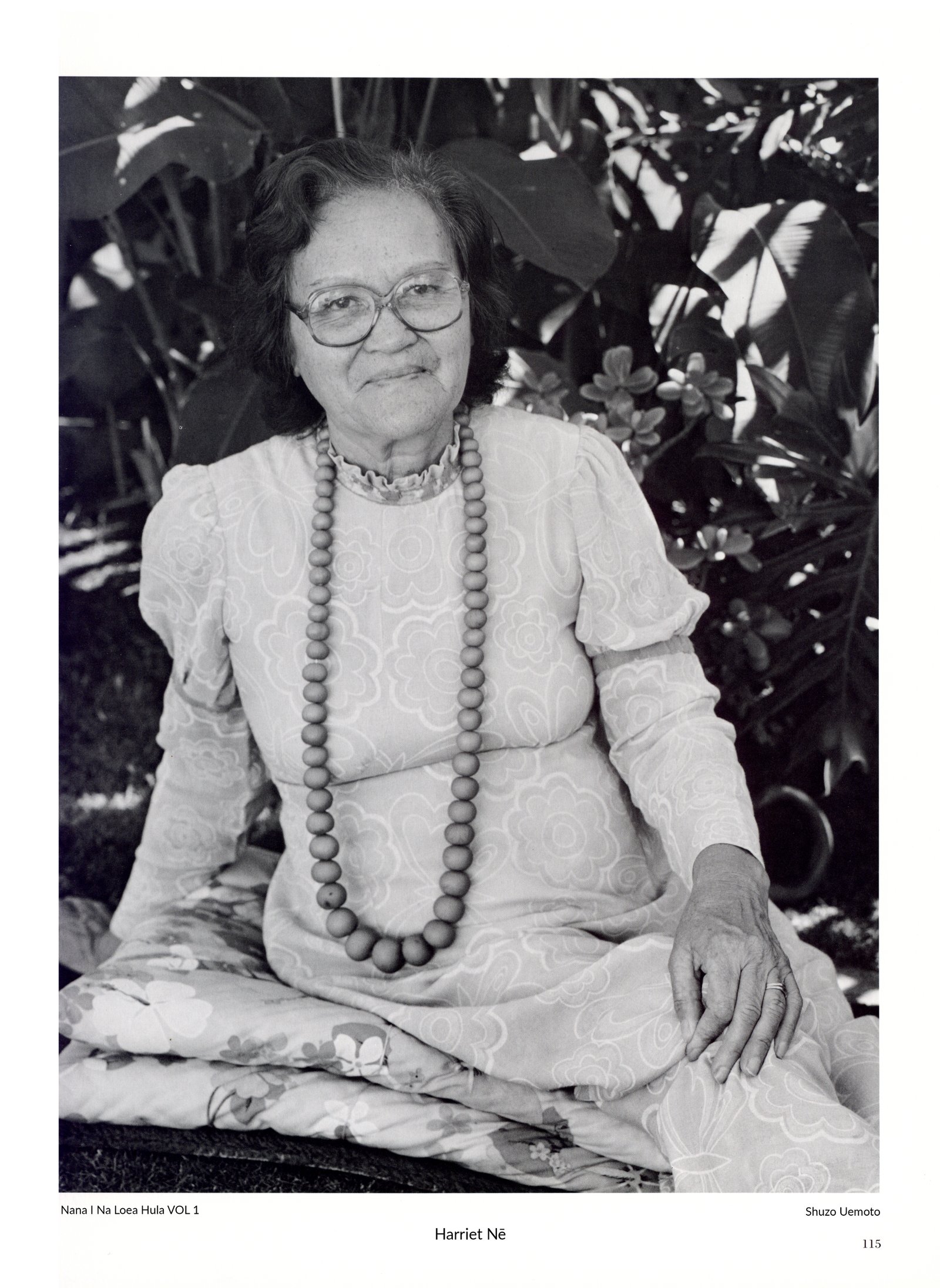

Harriet Nē

Title

Harriet Nē

Description

Harriet Nē

Harriet Nē has taught the traditional hula on the island of Moloka‘i for the past twenty-two years.

I was brought up in an atmosphere where male hula was taught. This was in the valley of Pelekunu on the east coast of Moloka‘i. I was born on O‘ahu but at four months I was taken back to Moloka‘i. I became interested in the hula at five because I had the opportunity to walk in and out of the hālau and watch the male dancers train. I had three uncles who had a hālau so I was permitted entrance. I learned to take my first steps to the beat of the pahu drum.

My first kumu was Ka‘ō‘ō of Moloka‘i. He taught me that you cannot do anything unless you have the right feeling within you. You can feel the vibration when your thoughts about the hula are correct. Ka‘ō‘ō would get inspired by going down to the ocean and then up into the mountains. Sometimes I would play by the seashore and watch him. One time I asked him what he was doing and he said he was waiting for the spirit to come into him and inspire him so he would know how to express the words. I was five-years-old when I started with Ka‘ō‘ō and he believed in training early in the morning. We would begin to train when the sun rose in the east. He would tell me that the sun is shining and another day is beginning where you are going to learn something new. Your heart and mind must be wide open to the acceptance of these teachings and that means you must discipline yourself to be open.

I stayed with Ka‘ō‘ō for nine years and then my family moved to Honolulu because Moloka‘i did not have a high school. We lived in Kaimukī on 9th Avenue and I went to a kumu named Kapele who was a big, husky hapa Haole who lived out in Kahalu‘u. Kapele gave every student special attention. He would encourage our strong points in class and work on our weaknesses out of class. I was confused at the time because my father was a Christian minister and he said I couldn’t be a Christian and dedicate myself to Laka at the same time. So after three years with Kapele he pulled me from the class.

I went on to Enoka Paleka in Kapahulu but after two years my father again pulled me from classes. My last kumu was Nanawai who taught me down at the Lalani Hawaiian Village on Paoakalani Avenue in Waikīkī. Nanawai was very good but he was a dreamer. He used to say to dance the hula you have to be a dreamer because you have to imagine yourself in another world, you have to visualize the mo‘olelo and kaona of the chant. It took me seven years with Nanawai before I was able to ‘ūniki.

I began teaching comic hula at age thirty-six because that’s all people were interested in at that time. In 1958 one of my uncles was dying at Lunalilo Home. I went to visit him and he asked me if I was teaching. I told him I was teaching children on Molokaʻi, and he instructed me to teach the Moloka’i Ku‘i and that it should be taught to the men of Molokaʻi first. He told me to come to the side of his bed and with a traditional Hawaiian ceremony he passed his talent onto me, the next generation in the family. I told him I didn’t know the Molokaʻi Kuʻi. He then got out of bed and performed the Moloka‘i Ku‘i step for me. He lay down on the bed and I think he was very happy because a few days later he passed away. I went home to Molokaʻi and I opened my hālau which was filled only with boys from Moloka‘i.

When I was growing up my nickname was “Lovely Hula Hands”. My aunty would tell me to be proud of my hands and I was always conscious of them. I was always taught that the palms of your hands should always face up because if they are turned down you will lose all your talent.

Every part of your body from your fingers to your feet should be signifying a part of your chant and I think that discipline is being lost. I think kahiko is becoming more commercialized. It’s alright for a student to take an unchoreographed kahiko chant and put motions to it as long as he or she understands and is faithful to each line in the chant. But there are kumu today that don’t understand the language and must learn it if they are going to continue. The language and the culture are the same. When I lived in Pelekunu I was exposed to a community that only spoke Hawaiian. When I moved from the valley I lived in a world that only spoke English and I began to lose my knowledge of the language. If you don’t know the language then you and your dancers are just making gestures. To me dancers are actors on a stage so in order to direct them a kumu must know the language, history, proper costuming, and the background of each dance. I have big arguments with kumu because they tell me we cannot stay traditional all the time. They say we have to move along with the times but it’s hard for me to see it their way.

Harriet Nē has taught the traditional hula on the island of Moloka‘i for the past twenty-two years.

I was brought up in an atmosphere where male hula was taught. This was in the valley of Pelekunu on the east coast of Moloka‘i. I was born on O‘ahu but at four months I was taken back to Moloka‘i. I became interested in the hula at five because I had the opportunity to walk in and out of the hālau and watch the male dancers train. I had three uncles who had a hālau so I was permitted entrance. I learned to take my first steps to the beat of the pahu drum.

My first kumu was Ka‘ō‘ō of Moloka‘i. He taught me that you cannot do anything unless you have the right feeling within you. You can feel the vibration when your thoughts about the hula are correct. Ka‘ō‘ō would get inspired by going down to the ocean and then up into the mountains. Sometimes I would play by the seashore and watch him. One time I asked him what he was doing and he said he was waiting for the spirit to come into him and inspire him so he would know how to express the words. I was five-years-old when I started with Ka‘ō‘ō and he believed in training early in the morning. We would begin to train when the sun rose in the east. He would tell me that the sun is shining and another day is beginning where you are going to learn something new. Your heart and mind must be wide open to the acceptance of these teachings and that means you must discipline yourself to be open.

I stayed with Ka‘ō‘ō for nine years and then my family moved to Honolulu because Moloka‘i did not have a high school. We lived in Kaimukī on 9th Avenue and I went to a kumu named Kapele who was a big, husky hapa Haole who lived out in Kahalu‘u. Kapele gave every student special attention. He would encourage our strong points in class and work on our weaknesses out of class. I was confused at the time because my father was a Christian minister and he said I couldn’t be a Christian and dedicate myself to Laka at the same time. So after three years with Kapele he pulled me from the class.

I went on to Enoka Paleka in Kapahulu but after two years my father again pulled me from classes. My last kumu was Nanawai who taught me down at the Lalani Hawaiian Village on Paoakalani Avenue in Waikīkī. Nanawai was very good but he was a dreamer. He used to say to dance the hula you have to be a dreamer because you have to imagine yourself in another world, you have to visualize the mo‘olelo and kaona of the chant. It took me seven years with Nanawai before I was able to ‘ūniki.

I began teaching comic hula at age thirty-six because that’s all people were interested in at that time. In 1958 one of my uncles was dying at Lunalilo Home. I went to visit him and he asked me if I was teaching. I told him I was teaching children on Molokaʻi, and he instructed me to teach the Moloka’i Ku‘i and that it should be taught to the men of Molokaʻi first. He told me to come to the side of his bed and with a traditional Hawaiian ceremony he passed his talent onto me, the next generation in the family. I told him I didn’t know the Molokaʻi Kuʻi. He then got out of bed and performed the Moloka‘i Ku‘i step for me. He lay down on the bed and I think he was very happy because a few days later he passed away. I went home to Molokaʻi and I opened my hālau which was filled only with boys from Moloka‘i.

When I was growing up my nickname was “Lovely Hula Hands”. My aunty would tell me to be proud of my hands and I was always conscious of them. I was always taught that the palms of your hands should always face up because if they are turned down you will lose all your talent.

Every part of your body from your fingers to your feet should be signifying a part of your chant and I think that discipline is being lost. I think kahiko is becoming more commercialized. It’s alright for a student to take an unchoreographed kahiko chant and put motions to it as long as he or she understands and is faithful to each line in the chant. But there are kumu today that don’t understand the language and must learn it if they are going to continue. The language and the culture are the same. When I lived in Pelekunu I was exposed to a community that only spoke Hawaiian. When I moved from the valley I lived in a world that only spoke English and I began to lose my knowledge of the language. If you don’t know the language then you and your dancers are just making gestures. To me dancers are actors on a stage so in order to direct them a kumu must know the language, history, proper costuming, and the background of each dance. I have big arguments with kumu because they tell me we cannot stay traditional all the time. They say we have to move along with the times but it’s hard for me to see it their way.

Citation

“Harriet Nē,” Nā Kumu Hula Archive, accessed February 25, 2026, https://nakumuhula.org/archive/items/show/75.