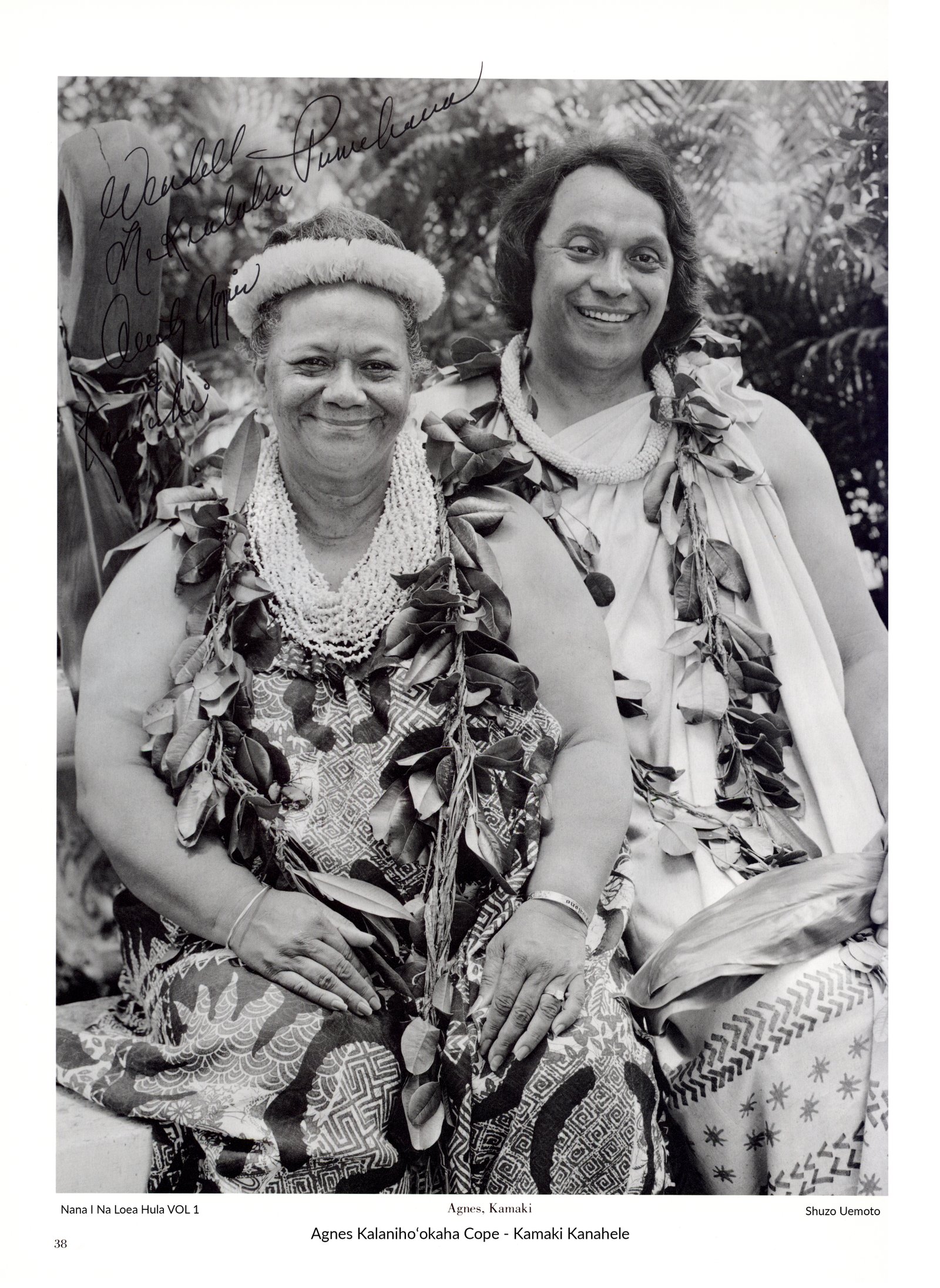

Agnes Kalaniho‘okaha Cope and Kamaki Kanahele

Title

Agnes Kalaniho‘okaha Cope and Kamaki Kanahele

Subject

Nā Kumu Hula Agnes Kalaniho‘okaha Cope and Kamaki Kanahele - Nānā I Nā Loea Hula Volume 1 Page 39

Description

Agnes Kalaniho‘okaha Cope

Agnes Cope is the executive director and founder of the Waianae Coast Culture and Arts Society.

My background in the hula started more than fifty years ago with Tūtū Keaka Kanahele. She was the grandmother of Eleanor Hiram Hoke and she was a hula master of the ’30s. Tūtū Keaka was our neighbor in Kalihi for many years, so it was easy for me to go through the backfence twice-a-week and attend practice. I started with the kahiko and in those days we had to put our hands up against the wall, bend our knees, and go down to the floor until the back of our heads touched the ground. Then Tūtū Keaka would have us rise to our feet and repeat the motion until she was satisfied. It was the old way of training as far as I know of. I practiced with Tūtū Keaka for many years in Kalihi on Mokauea Street and then she moved to King Street where my classes continued every Saturday for four hours. My training lasted fifteen years and it wasn’t until 1969 that I went to another kumu. I must pay tribute to my mother Sarah Kalaniho‘okaha Haku‘ole Mengler and my father Henry T. Mengler who permitted me to attend hula classes and gave me the support and encouragement that I needed at that time.

In 1969, the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts asked ‘Iolani Luahine and Lokalia Montgomery to select someone to leave their knowledge to. Everyone knew there was Hoakalei Kamau‘u to step into Aunty ‘Io’s place but there was no one for Lokalia. At a conference in Kona at the Hale Hālāwai, Lokalia asked fifteen of us to her home for lunch. At her home she announced that I was the one she had chosen. I told her she had to make another choice because I had other obligations. She pounded the table and said if I was not going to accept, she would take her knowledge with her. So I stayed in Kona for one year, coming home every other week to work and be with my family. My training with her lasted from dawn to dusk, six days a week. If I was on the fourteenth verse of a fifteen-verse chant and made a mistake, I would have to go back and start all over again from the first verse. During my training Lokalia prepared all my meals and did everything for me. If I wanted even a glass of water, Lokalia would serve it to me. All that was asked of me was to train and concentrate. She left with me many chants that have not been heard of. There came a time when the arthritis in my legs began to bother me and I couldn’t bend or rise. At that point my son Kamaki took my place and continued on with her.

There is nothing that can compare with the hula lessons that I received from these two great masters. I would like to pay tribute to Tūtū Keaka and Tūtū Lokalia for their efforts, support, and the opportunity they presented me to study the hula under their guidance.

Kamaki Kanahele

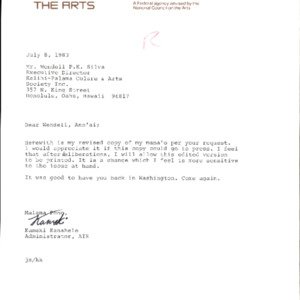

Kamaki Kanahele, son of Mrs. Agnes K. Cope, is currently the administrator of the National Endowment for the Arts, Education Program, in Washington, D.C.

I didn’t realize I was interested in the hula because I was already doing it as a part of my everyday life. To me it was normal. My mother and grandparents were my first teachers and we were raised to move, sit right, stand right, and speak correctly. To understand these things is an important part of life. We not only learned basic movements but with it came the use of herbs for healing purposes. This also became a natural learning experience. We were taught the importance of healing the body then developing it. Gathering herbs, chanting its purposes and processes of cleansing and healing, and thanking ke akua, always thanking ke akua. The healing was called lā‘au lapa‘au, lā‘au kahea, ho‘oponopono, lomilomi, and more. The developing was called oilioli, hākōkō, na pa’alula, running, swimming, short-long breathing techniques, concentrating on the na‘au, and many more. Our other games were imitating animals of the land, sea, and sky, and always talking to and thanking ke akua. We learned by watching and repeating. Sometimes doing it daily or only in the mornings. As children we practiced our healing lessons on our dogs. They were very good patients and because we loved them the healing lessons were very wonderful. My grandparents also taught me the closed art of ‘anā‘anā. Our responsibility was to nail the army blankets to the windows to block out the windows. My tūtū said that this lesson was not to be spoken of. We would let he or a visiting kahuna do his work and we just had to watch and learn. All Tūtū said was that this was a necessary part of life. We were always taught with strict observance the protocol of this very ancient art form. In sickness we healed ourselves. For somethings you can heal and cleanse, for others we must return to the teacher or suffer from kāpulu work. We never realized what we had learned or been given until we were adults. Like all children we just wanted to play. Our lessons were our games.

In 1963 I went to the Church College of Hawai’i and worked under Aunty Sally Wood Nālua’i and also learned from Aunty Emma Paishon. In that time I worked under the tutorage of George Nā‘ope also. Finally I came to Grandma Lokalia Montgomery. She finished my formal training in the hula kahiko. She told me that I would be her last formally trained student. My family had taught me that the feeling for hula should come from within you, Grandma Lokalia took the feelings of hula and formalized it. She put it into a specific class. It was then that I came to realize that all the things that I had been taught belonged into separate categories under different standards and yet all of it was one in life. To know that each had its own mana‘o, formidable and controlled, Grandma had taken me and had gone over the entire structure of hula. Everything had its place. She was hard-nosed, no- nonsense, and stout. She would summon me at any time of the day or night. So out from Lā‘ie I would drive. I learned that the hula is not just merely getting up to dance or to perform. Instead everytime you stood to dance or sat to chant it was your responsibility to summarize life and hint at its happiness and sadness. Describe the good and the bad, make a beginning, and end it with pride. The dancer becomes an ali‘i, a god, a shark, or a dog. They can be beautiful or arrogant, handsome or ugly. You give the human being a glimpse of his time on earth with a repeat of these reminders each time he comes to the floor. My training took four years and became an image of my upbringing.

Grandma gave me an ‘uniki that was personal and loving. For her, my mother, and for all things I thank ke akua. Before her death, Grandma gave me her collection of chants, tableaus, hula notes, compositions, and her love.

Aloha ke akua.

Our kumu were trained under the structure that was similar and yet distinct from island to island.

It is the structure that we must identify and have as a foundation and preserve what has been handed down in hula kahiko. When that precedent is set then everything thereafter becomes ‘auwana. It is healthy for our youth to move beyond this foundation once set. For they have their time in life. They must experience the turtle, the shark, healing, and power. It is unhealthy to state that that structure is binding upon everyone and therefore limit creativity. It is and should be considered an ancestral seed by which to grow. Hula must always have its piko, its center of balance. It is a living energy and a beckoning force. There will always be controversy about what is proper or correct, but a demonstration of the unity of hula in our time can only solidify the remnants of what is left of a great heritage.

I feel that the youth, the breath of our life, is giving to us the breath of our dignity. Our contributions then to them is to give what we have as a ho’okupu. It can only make their reach in life a little more comfortable.

Agnes Cope is the executive director and founder of the Waianae Coast Culture and Arts Society.

My background in the hula started more than fifty years ago with Tūtū Keaka Kanahele. She was the grandmother of Eleanor Hiram Hoke and she was a hula master of the ’30s. Tūtū Keaka was our neighbor in Kalihi for many years, so it was easy for me to go through the backfence twice-a-week and attend practice. I started with the kahiko and in those days we had to put our hands up against the wall, bend our knees, and go down to the floor until the back of our heads touched the ground. Then Tūtū Keaka would have us rise to our feet and repeat the motion until she was satisfied. It was the old way of training as far as I know of. I practiced with Tūtū Keaka for many years in Kalihi on Mokauea Street and then she moved to King Street where my classes continued every Saturday for four hours. My training lasted fifteen years and it wasn’t until 1969 that I went to another kumu. I must pay tribute to my mother Sarah Kalaniho‘okaha Haku‘ole Mengler and my father Henry T. Mengler who permitted me to attend hula classes and gave me the support and encouragement that I needed at that time.

In 1969, the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts asked ‘Iolani Luahine and Lokalia Montgomery to select someone to leave their knowledge to. Everyone knew there was Hoakalei Kamau‘u to step into Aunty ‘Io’s place but there was no one for Lokalia. At a conference in Kona at the Hale Hālāwai, Lokalia asked fifteen of us to her home for lunch. At her home she announced that I was the one she had chosen. I told her she had to make another choice because I had other obligations. She pounded the table and said if I was not going to accept, she would take her knowledge with her. So I stayed in Kona for one year, coming home every other week to work and be with my family. My training with her lasted from dawn to dusk, six days a week. If I was on the fourteenth verse of a fifteen-verse chant and made a mistake, I would have to go back and start all over again from the first verse. During my training Lokalia prepared all my meals and did everything for me. If I wanted even a glass of water, Lokalia would serve it to me. All that was asked of me was to train and concentrate. She left with me many chants that have not been heard of. There came a time when the arthritis in my legs began to bother me and I couldn’t bend or rise. At that point my son Kamaki took my place and continued on with her.

There is nothing that can compare with the hula lessons that I received from these two great masters. I would like to pay tribute to Tūtū Keaka and Tūtū Lokalia for their efforts, support, and the opportunity they presented me to study the hula under their guidance.

Kamaki Kanahele

Kamaki Kanahele, son of Mrs. Agnes K. Cope, is currently the administrator of the National Endowment for the Arts, Education Program, in Washington, D.C.

I didn’t realize I was interested in the hula because I was already doing it as a part of my everyday life. To me it was normal. My mother and grandparents were my first teachers and we were raised to move, sit right, stand right, and speak correctly. To understand these things is an important part of life. We not only learned basic movements but with it came the use of herbs for healing purposes. This also became a natural learning experience. We were taught the importance of healing the body then developing it. Gathering herbs, chanting its purposes and processes of cleansing and healing, and thanking ke akua, always thanking ke akua. The healing was called lā‘au lapa‘au, lā‘au kahea, ho‘oponopono, lomilomi, and more. The developing was called oilioli, hākōkō, na pa’alula, running, swimming, short-long breathing techniques, concentrating on the na‘au, and many more. Our other games were imitating animals of the land, sea, and sky, and always talking to and thanking ke akua. We learned by watching and repeating. Sometimes doing it daily or only in the mornings. As children we practiced our healing lessons on our dogs. They were very good patients and because we loved them the healing lessons were very wonderful. My grandparents also taught me the closed art of ‘anā‘anā. Our responsibility was to nail the army blankets to the windows to block out the windows. My tūtū said that this lesson was not to be spoken of. We would let he or a visiting kahuna do his work and we just had to watch and learn. All Tūtū said was that this was a necessary part of life. We were always taught with strict observance the protocol of this very ancient art form. In sickness we healed ourselves. For somethings you can heal and cleanse, for others we must return to the teacher or suffer from kāpulu work. We never realized what we had learned or been given until we were adults. Like all children we just wanted to play. Our lessons were our games.

In 1963 I went to the Church College of Hawai’i and worked under Aunty Sally Wood Nālua’i and also learned from Aunty Emma Paishon. In that time I worked under the tutorage of George Nā‘ope also. Finally I came to Grandma Lokalia Montgomery. She finished my formal training in the hula kahiko. She told me that I would be her last formally trained student. My family had taught me that the feeling for hula should come from within you, Grandma Lokalia took the feelings of hula and formalized it. She put it into a specific class. It was then that I came to realize that all the things that I had been taught belonged into separate categories under different standards and yet all of it was one in life. To know that each had its own mana‘o, formidable and controlled, Grandma had taken me and had gone over the entire structure of hula. Everything had its place. She was hard-nosed, no- nonsense, and stout. She would summon me at any time of the day or night. So out from Lā‘ie I would drive. I learned that the hula is not just merely getting up to dance or to perform. Instead everytime you stood to dance or sat to chant it was your responsibility to summarize life and hint at its happiness and sadness. Describe the good and the bad, make a beginning, and end it with pride. The dancer becomes an ali‘i, a god, a shark, or a dog. They can be beautiful or arrogant, handsome or ugly. You give the human being a glimpse of his time on earth with a repeat of these reminders each time he comes to the floor. My training took four years and became an image of my upbringing.

Grandma gave me an ‘uniki that was personal and loving. For her, my mother, and for all things I thank ke akua. Before her death, Grandma gave me her collection of chants, tableaus, hula notes, compositions, and her love.

Aloha ke akua.

Our kumu were trained under the structure that was similar and yet distinct from island to island.

It is the structure that we must identify and have as a foundation and preserve what has been handed down in hula kahiko. When that precedent is set then everything thereafter becomes ‘auwana. It is healthy for our youth to move beyond this foundation once set. For they have their time in life. They must experience the turtle, the shark, healing, and power. It is unhealthy to state that that structure is binding upon everyone and therefore limit creativity. It is and should be considered an ancestral seed by which to grow. Hula must always have its piko, its center of balance. It is a living energy and a beckoning force. There will always be controversy about what is proper or correct, but a demonstration of the unity of hula in our time can only solidify the remnants of what is left of a great heritage.

I feel that the youth, the breath of our life, is giving to us the breath of our dignity. Our contributions then to them is to give what we have as a ho’okupu. It can only make their reach in life a little more comfortable.

Citation

“Agnes Kalaniho‘okaha Cope and Kamaki Kanahele,” Nā Kumu Hula Archive, accessed February 14, 2026, https://nakumuhula.org/archive/items/show/40.