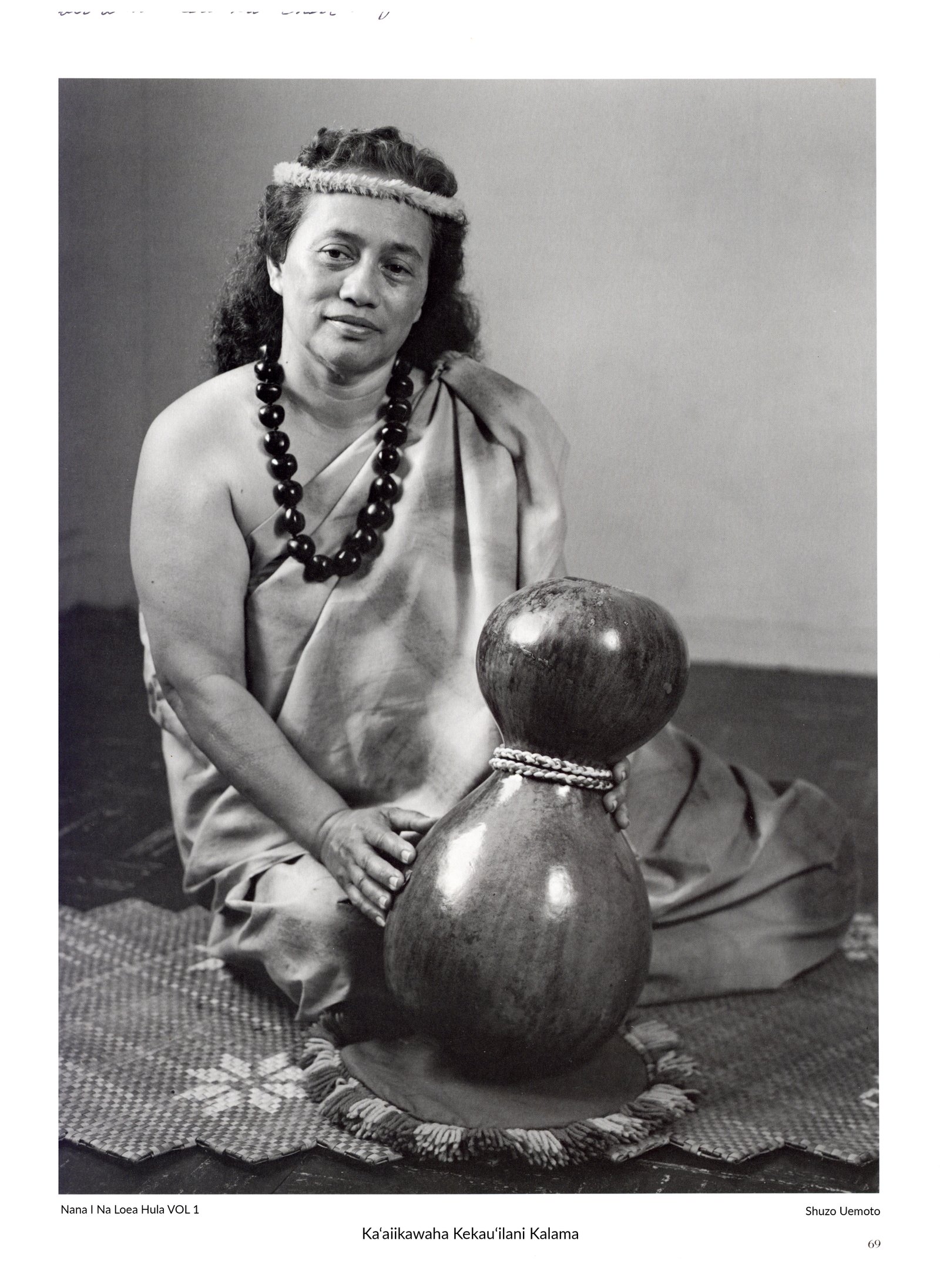

Ka‘aiikawaha Kekau‘ilani Kalama

Title

Ka‘aiikawaha Kekau‘ilani Kalama

Description

Ka‘aiikawaha Kekauʻilani Kalama

Lani Kalama, cousin of Māiki Aiu Lake, serves as a hula consultant for various hula halaus throughout Hawaii. She currently resides in Kailua, O‘ahu.

When I was fifteen-years-old, my friend Nellie Wong told me she had heard of a lady named Lokalia Montgomery who was teaching the hula pahu in Kapahulu. My yearning to further my knowledge in the hula prompted me to pay fourteen dollars to learn which was a lot of money in those days. I didn’t dare ask my grandmother because I was sure she wouldn’t let me, so I broke my piggy bank and I took that money to Lokalia to pay for my lessons.

My formal hula training actually began at the age of seven under Tūtū Keaka Kanahele and Gertrude Makini at Aunty Gertrudes home on Rose Street. The class was made up of all the neighborhood children and the kids in my family. The Makinis’ had a big yard and a large home and we would move all the chairs in the living room, and that’s where we would dance. We would go to class everyday and if Tūtū felt like it we were there for hours. If she was tired the class would be cancelled for three or four days. I graduated traditionally with Aunty Gertrude and then I went on to Harriet Kepelino Fernandez who trained me in hula ‘auwana. I went through the hula kapu training with Aunty Harriet but when it came time to perform the rituals myself my grandmother stopped me. I am especially grateful to my grandmother Helen Pamaiēulu Ha‘o Correa who exposed me to the hula at a very tender age. She made me aware of the mannerisms and protocol of the hula because back then the definition of hula ‘auwana meant hula that was free of any ritual ceremony or kapu and had nothing to do with creativity or musical accompaniment.

I graduated traditionally from Aunty Harriet at fourteen but I wanted to study more of the hula pahu and that is how I was led to Lokalia Montgomery. In Lokalia’s dining room she had a great dinner table where she would talk with her guests. Beautiful Hawaiian ladies such as Kawena Pūku‘i, Malia Kau, and Vickie I‘i would drop in throughout the day to “talk story” and we would be in the dancing area which was separated by a sliding door waiting to learn. One day I decided to be the teacher and I had the girls dance as I chanted and beat the drum. She returned sooner than I expected and she told me from that day on I would have to learn both the chant and the dance.

One night there was a chant I really wanted to learn so I sat in my room in the dark and beat my pahu softly and chanted to myself. After awhile I got so involved I began pounding my drum and chanting full-voice. Before I knew it the door was open and my grandmother was standing there. Up until that evening no one in my family had any idea I was learning the hula pahu and I thought that was it for me. I told her about the piggy bank and Lokalia and she began to cry. She told me that her father had proclaimed that their future lay in the Christian world. No one was encouraged to go into the Hawaiian culture. But he prophesied that despite all this suppression, one of his descendants would come out of it and I turned out to be the one. I was sixteen at the time and my grandmother said she wanted to meet this Lokalia.

Under Lokalia we were never allowed to write anything. We never received a copy of a translation; she just taught and we just listened. Her descriptions and translations were all in-tune with nature. Lokalia said her mentor was Kawena Pūku‘i and there were no teaching differences between Keaka Kanahele and Lokalia so I consider my hula kahiko to be a continuation of the Keaka Kanahele-Kawena Pūku‘i- Lokalia Montgomery line. In preparation for our ‘ūniki our last practice was held at midnight before the next day’s ceremony. Sally Wood Nālua‘i was married and so she was permitted to go home but the rest of us had to spend the night at Lokalia’s home. All of our implements were made by Timothy Montgomery, Lokalia’s husband, and our clothing was made by Lokalia. On the day of the ‘ūniki we had a little pā‘ina in the living room which was followed by a public ceremony to which all of our friends and relatives were invited.

I began to teach the hula in 1948 in the parish hall of the Blessed Sacrament Church in Pauoa as a means of adding to my family’s livelihood. I was married and I was starting a family and 1 taught the parishioners of the Church. Through the years I have kept myself involved with the hula but always my first obligation was to my family and my husband Charles Kalama. I consider myself a contemporary hula teacher and not a kumu hula. I think the word kumu is used too loosely today. I’m only a branch of the tree. My teachers were the real kumu. To be a real teacher you cannot have two lives. You cannot be married or have a family because your life has to be dedicated to your students.

I am grateful to many people who shared their knowledge with me. My mama Hoakalei deFries had patience with me, Pilahi Paki gave me a foundation in the Hawaiian language, and Gertrude Makini and Harriet Kepelino gave me my training in hula ‘auwana. Someone told me that people have to express their creativity and you have to have modern thinking today. But I feel we have to remember the past. That doesn’t mean we remain in the past but without our traditional ways we have no foundation. The question that is repeatedly asked today is how do we know what is traditional? There are a few people who lived during those times and were taught by the hula masters of yesterday. I am asking the kumu hula of today to have faith and a belief in them.

Lani Kalama, cousin of Māiki Aiu Lake, serves as a hula consultant for various hula halaus throughout Hawaii. She currently resides in Kailua, O‘ahu.

When I was fifteen-years-old, my friend Nellie Wong told me she had heard of a lady named Lokalia Montgomery who was teaching the hula pahu in Kapahulu. My yearning to further my knowledge in the hula prompted me to pay fourteen dollars to learn which was a lot of money in those days. I didn’t dare ask my grandmother because I was sure she wouldn’t let me, so I broke my piggy bank and I took that money to Lokalia to pay for my lessons.

My formal hula training actually began at the age of seven under Tūtū Keaka Kanahele and Gertrude Makini at Aunty Gertrudes home on Rose Street. The class was made up of all the neighborhood children and the kids in my family. The Makinis’ had a big yard and a large home and we would move all the chairs in the living room, and that’s where we would dance. We would go to class everyday and if Tūtū felt like it we were there for hours. If she was tired the class would be cancelled for three or four days. I graduated traditionally with Aunty Gertrude and then I went on to Harriet Kepelino Fernandez who trained me in hula ‘auwana. I went through the hula kapu training with Aunty Harriet but when it came time to perform the rituals myself my grandmother stopped me. I am especially grateful to my grandmother Helen Pamaiēulu Ha‘o Correa who exposed me to the hula at a very tender age. She made me aware of the mannerisms and protocol of the hula because back then the definition of hula ‘auwana meant hula that was free of any ritual ceremony or kapu and had nothing to do with creativity or musical accompaniment.

I graduated traditionally from Aunty Harriet at fourteen but I wanted to study more of the hula pahu and that is how I was led to Lokalia Montgomery. In Lokalia’s dining room she had a great dinner table where she would talk with her guests. Beautiful Hawaiian ladies such as Kawena Pūku‘i, Malia Kau, and Vickie I‘i would drop in throughout the day to “talk story” and we would be in the dancing area which was separated by a sliding door waiting to learn. One day I decided to be the teacher and I had the girls dance as I chanted and beat the drum. She returned sooner than I expected and she told me from that day on I would have to learn both the chant and the dance.

One night there was a chant I really wanted to learn so I sat in my room in the dark and beat my pahu softly and chanted to myself. After awhile I got so involved I began pounding my drum and chanting full-voice. Before I knew it the door was open and my grandmother was standing there. Up until that evening no one in my family had any idea I was learning the hula pahu and I thought that was it for me. I told her about the piggy bank and Lokalia and she began to cry. She told me that her father had proclaimed that their future lay in the Christian world. No one was encouraged to go into the Hawaiian culture. But he prophesied that despite all this suppression, one of his descendants would come out of it and I turned out to be the one. I was sixteen at the time and my grandmother said she wanted to meet this Lokalia.

Under Lokalia we were never allowed to write anything. We never received a copy of a translation; she just taught and we just listened. Her descriptions and translations were all in-tune with nature. Lokalia said her mentor was Kawena Pūku‘i and there were no teaching differences between Keaka Kanahele and Lokalia so I consider my hula kahiko to be a continuation of the Keaka Kanahele-Kawena Pūku‘i- Lokalia Montgomery line. In preparation for our ‘ūniki our last practice was held at midnight before the next day’s ceremony. Sally Wood Nālua‘i was married and so she was permitted to go home but the rest of us had to spend the night at Lokalia’s home. All of our implements were made by Timothy Montgomery, Lokalia’s husband, and our clothing was made by Lokalia. On the day of the ‘ūniki we had a little pā‘ina in the living room which was followed by a public ceremony to which all of our friends and relatives were invited.

I began to teach the hula in 1948 in the parish hall of the Blessed Sacrament Church in Pauoa as a means of adding to my family’s livelihood. I was married and I was starting a family and 1 taught the parishioners of the Church. Through the years I have kept myself involved with the hula but always my first obligation was to my family and my husband Charles Kalama. I consider myself a contemporary hula teacher and not a kumu hula. I think the word kumu is used too loosely today. I’m only a branch of the tree. My teachers were the real kumu. To be a real teacher you cannot have two lives. You cannot be married or have a family because your life has to be dedicated to your students.

I am grateful to many people who shared their knowledge with me. My mama Hoakalei deFries had patience with me, Pilahi Paki gave me a foundation in the Hawaiian language, and Gertrude Makini and Harriet Kepelino gave me my training in hula ‘auwana. Someone told me that people have to express their creativity and you have to have modern thinking today. But I feel we have to remember the past. That doesn’t mean we remain in the past but without our traditional ways we have no foundation. The question that is repeatedly asked today is how do we know what is traditional? There are a few people who lived during those times and were taught by the hula masters of yesterday. I am asking the kumu hula of today to have faith and a belief in them.

Citation

“Ka‘aiikawaha Kekau‘ilani Kalama,” Nā Kumu Hula Archive, accessed February 14, 2026, https://nakumuhula.org/archive/items/show/54.