Samuel (Kamuela) Nae‘ole

Title

Samuel (Kamuela) Nae‘ole

Description

Samuel (Kamuela) Nae‘ole

The late Sam Naeʻole taught the hula in Hawaii for twenty-six years. He was affiliated with the Kalihi-Pālama Culture & Arts Society as a kumu hula and is credited with pioneering the hula in the Hawaiian Homestead of Waimanalo, O‘ahu.

My mother and aunty were dream translators in the Hawaiian community and I told them I had dreamt I had been taken to a great house. Within the house was an old man who beckoned me to come in. They told me that this was a sign that I was the chosen one to carry on the spirit of the old man’s body. The next day I went to hula class and Lokalia (Montgomery) told me to stay late. She drove me out of Kapahulu and we came to the same house that I had dreamt of the night before. When we entered the home she was greeted by an old man who introduced himself as Joseph ‘Īlālā’ole. He was dying at the time and he had asked Lokalia to bring him a male student to train.

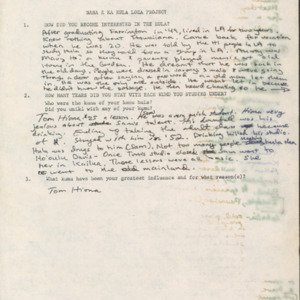

My aunty Mary Ho was a kumu hula and my parents were musicians at the old Home in The Garden, but I wasn’t interested in the culture and when 1 graduated from Farrington High School in 1949 I knew nothing about it. I moved to Los Angeles and in 19511 came back home for a vacation. I was asked by other Hawai'i people in Los Angeles to study hula so I could come back and teach. So I went to the phone book and looked for a male teacher and the name I found was Tom Hiona. His studio was located on Maunakea and King Street and he charged twenty-five dollars a lesson. Tom had been trained by Kau‘i Zuttermeister but he was something original and extraordinary. His mind was always filled with ideas that raised the hula to higher ground. As far as I know he was the first person to produce tableaus and pageants that dealt with the culture in a deeper and more profound way.

I stayed with Tom until 1952 when he closed his studio, and I went on to Ho‘oulu Davis in Kailua but within a year she left and I was out in the cold again. After Ho‘oulu I informally studied under Kawena Pūku‘i in Kaimukī. My father would take me to work with him at daybreak and I would be dropped off at St. Louis High School. From there I would walk to Mrs. Pūku‘i’s home and for three dollars I would be taught one song. She would ask me to choose four subjects to write about and this was how I was encouraged and trained to write hula songs and traditional chants. I went on to train informally under Kathy Nākaula, Joseph ‘Īlālā’ole, Pua Haʻaheo, and Ka‘o‘o, but my next formal teacher was Lokalia Montgomery.

In 1954 Lokalia Montgomery charged a pre-paid tuition of four hundred dollars and I didn’t have the money. So I saved what I could and sold the only possession I had that was worth anything which was my piano. Lokalia lived off Kapahulu Avenue in a big white house and we were trained five days a week from 8:30 in the morning till 2:30 in the afternoon with a thirty- minute lunch. The majority of her students were Japanese from the University who were taking lessons as part of an Asian studies requirement for graduation. We would be trained in her big parlour where we were first taught the different beats on the ipu and then she would give us one chant to learn. We would recite the chant and she would correct us as we went along. In the old days the kumu would transfer their spirit into the body of their students but Lokalia did not believe in this. We were responsible for making our own implements so Lokalia’s husband Timothy taught us how to dye material, paint, and produce traditional Hawaiian crafts.

I did not ‘ūniki with any of my teachers because the graduation ceremony with the traditional rituals was not popular back in the Forties and Fifties. If a student graduated traditionally their kumu would have to carry the burden if a haumāna broke a kapu and nobody really wanted any part of that. Today the emphasis seems to be on the ‘ūniki but my advice to the young dancers is go back to the kupuna to get your legitimacy. Degrees count for very little in the hula community.

I began to teach in Waimanalo in 1955 with the encouragement of friends. I charged three dollars a month for each student, and I’ve tried to teach by nurturing the positive in my haumāna. I never had an abundance of anything but I’ve never had to endure a difficult, terrible period either. I’ve tried to teach the younger people the true knowledge of the hula and I’ve looked upon that as an opportunity.

The hula that is being perpetuated today as the traditional hula of our culture is a figment of someone’s imagination. A great majority of the kumu today are only on the level of students and the result is that the modern audience of today has never seen the traditional hula. Hopefully, people will get tired of all this fluff and make an effort to start finding out what is authentic and what is baloney.

The late Sam Naeʻole taught the hula in Hawaii for twenty-six years. He was affiliated with the Kalihi-Pālama Culture & Arts Society as a kumu hula and is credited with pioneering the hula in the Hawaiian Homestead of Waimanalo, O‘ahu.

My mother and aunty were dream translators in the Hawaiian community and I told them I had dreamt I had been taken to a great house. Within the house was an old man who beckoned me to come in. They told me that this was a sign that I was the chosen one to carry on the spirit of the old man’s body. The next day I went to hula class and Lokalia (Montgomery) told me to stay late. She drove me out of Kapahulu and we came to the same house that I had dreamt of the night before. When we entered the home she was greeted by an old man who introduced himself as Joseph ‘Īlālā’ole. He was dying at the time and he had asked Lokalia to bring him a male student to train.

My aunty Mary Ho was a kumu hula and my parents were musicians at the old Home in The Garden, but I wasn’t interested in the culture and when 1 graduated from Farrington High School in 1949 I knew nothing about it. I moved to Los Angeles and in 19511 came back home for a vacation. I was asked by other Hawai'i people in Los Angeles to study hula so I could come back and teach. So I went to the phone book and looked for a male teacher and the name I found was Tom Hiona. His studio was located on Maunakea and King Street and he charged twenty-five dollars a lesson. Tom had been trained by Kau‘i Zuttermeister but he was something original and extraordinary. His mind was always filled with ideas that raised the hula to higher ground. As far as I know he was the first person to produce tableaus and pageants that dealt with the culture in a deeper and more profound way.

I stayed with Tom until 1952 when he closed his studio, and I went on to Ho‘oulu Davis in Kailua but within a year she left and I was out in the cold again. After Ho‘oulu I informally studied under Kawena Pūku‘i in Kaimukī. My father would take me to work with him at daybreak and I would be dropped off at St. Louis High School. From there I would walk to Mrs. Pūku‘i’s home and for three dollars I would be taught one song. She would ask me to choose four subjects to write about and this was how I was encouraged and trained to write hula songs and traditional chants. I went on to train informally under Kathy Nākaula, Joseph ‘Īlālā’ole, Pua Haʻaheo, and Ka‘o‘o, but my next formal teacher was Lokalia Montgomery.

In 1954 Lokalia Montgomery charged a pre-paid tuition of four hundred dollars and I didn’t have the money. So I saved what I could and sold the only possession I had that was worth anything which was my piano. Lokalia lived off Kapahulu Avenue in a big white house and we were trained five days a week from 8:30 in the morning till 2:30 in the afternoon with a thirty- minute lunch. The majority of her students were Japanese from the University who were taking lessons as part of an Asian studies requirement for graduation. We would be trained in her big parlour where we were first taught the different beats on the ipu and then she would give us one chant to learn. We would recite the chant and she would correct us as we went along. In the old days the kumu would transfer their spirit into the body of their students but Lokalia did not believe in this. We were responsible for making our own implements so Lokalia’s husband Timothy taught us how to dye material, paint, and produce traditional Hawaiian crafts.

I did not ‘ūniki with any of my teachers because the graduation ceremony with the traditional rituals was not popular back in the Forties and Fifties. If a student graduated traditionally their kumu would have to carry the burden if a haumāna broke a kapu and nobody really wanted any part of that. Today the emphasis seems to be on the ‘ūniki but my advice to the young dancers is go back to the kupuna to get your legitimacy. Degrees count for very little in the hula community.

I began to teach in Waimanalo in 1955 with the encouragement of friends. I charged three dollars a month for each student, and I’ve tried to teach by nurturing the positive in my haumāna. I never had an abundance of anything but I’ve never had to endure a difficult, terrible period either. I’ve tried to teach the younger people the true knowledge of the hula and I’ve looked upon that as an opportunity.

The hula that is being perpetuated today as the traditional hula of our culture is a figment of someone’s imagination. A great majority of the kumu today are only on the level of students and the result is that the modern audience of today has never seen the traditional hula. Hopefully, people will get tired of all this fluff and make an effort to start finding out what is authentic and what is baloney.

Citation

“Samuel (Kamuela) Nae‘ole,” Nā Kumu Hula Archive, accessed February 14, 2026, https://nakumuhula.org/archive/items/show/72.