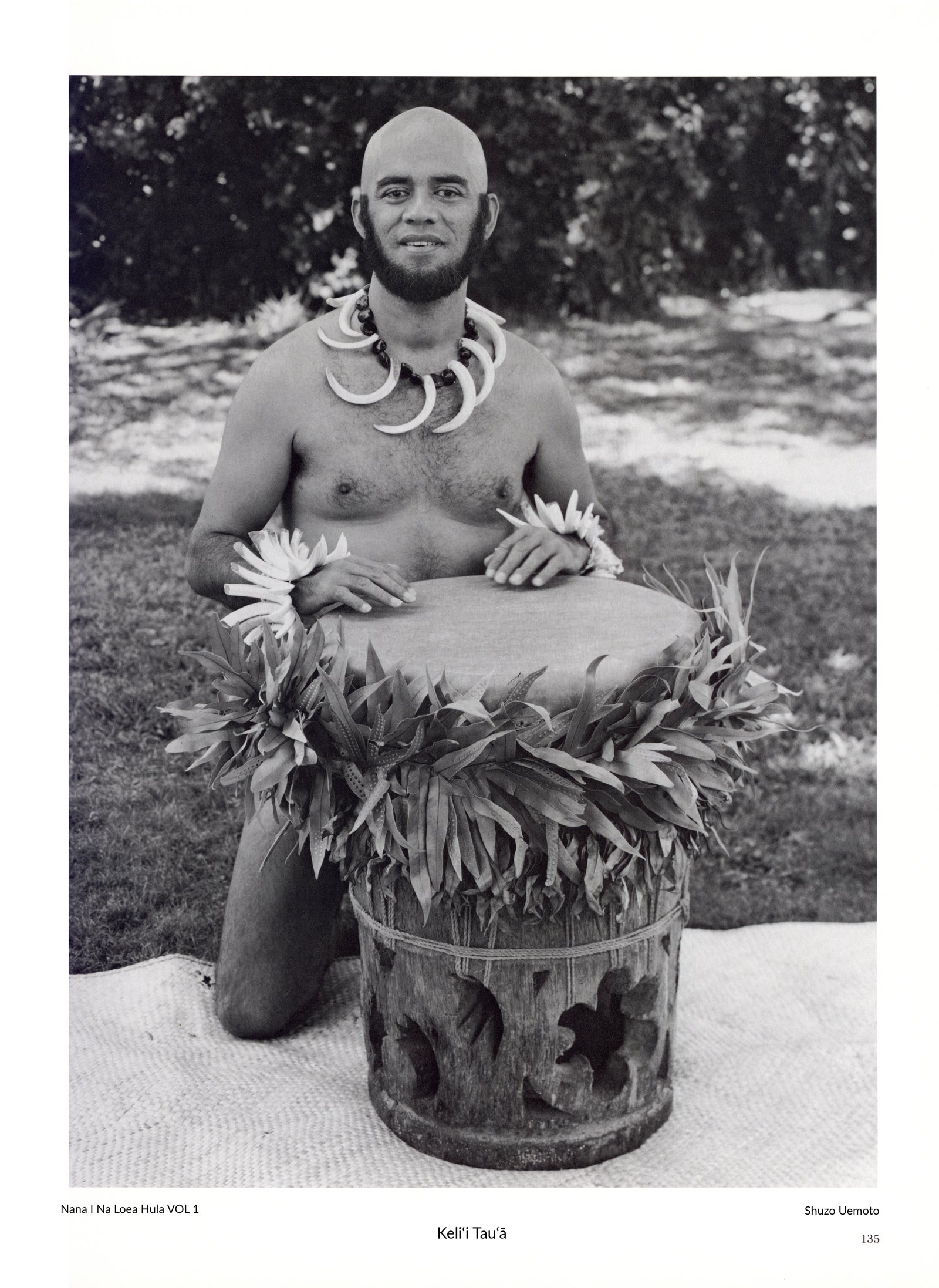

Keli‘i Tau‘ā

Title

Keli‘i Tau‘ā

Description

Keli‘i Tau‘ā

Keli‘i Tau‘ā has taught the hula on O‘ahu for the past five years and currently makes his home in Kihei, Maui.

I think the biggest stumbling block for the modern Hawaiian is the definition of who is and who is not Hawaiian. Many people still believe it is strictly a matter of race. Today being Hawaiian has more to do with a sincerity of feeling towards the fate of Hawai‘i than anything else.

In 1970 I was teaching Hawaiiana for the Department of Education at Waimanalo Intermediate School. Aunty Nona Beamer was serving as my consultant. I was required to learn hula for teaching purposes and so Aunty Nona invited me to train under her informally. I stayed with her for a year and in 1972 Aunty Mā‘iki Aiu publicly announced that she would be holding classes for hula teachers.

The hālau at that time was on Ke‘eaumoku Street and after some practices, I could hardly walk down the stairs of the second- floor studio. The “Hawaiian Renaissance” to coin a phrase of that time, was just starting to turn its wheels. Anything that was Hawaiian was a joy to learn.

I think the greatest thing that I came to recognize was that hula was not just motions but Hawaiian life, language, and folklore. That was the greatest joy, being in a place where I was learning not only the dance but something about myself in relationship to the past Hawaiian culture. What was there, and what it could be in the future.

More answers came from another kumu named Kau‘i Zuttermeister. I started studying intensively in 1973 with style and a feeling that I still possess today and transfer the stylings of Aunty Kau‘i to others. I started to teach in 1975. Two of my former classmates in Aunty Mā‘iki’s hālau, Robert Cazimero, and John Topolinski were really getting into men’s hula and it was exciting to me. There had been men’s hula when we were learning but there weren’t hālaus as we understand it today. They set the pace and helped to establish respectability for men to dance.

My approach was to show that hula was physical and demanding and required dedication and learning. That’s how in 1978 I ended up with a hālau of fifty- five men, half of them college or professional football players. My work has centered on kahiko because ‘auwana, as the word indicates, can be created by anyone, anytime, anywhere. My definition of hula kahiko is that of Edith Kanakaʻole’s. It would have to be movements passed down from generation to generation.

In the old days we were taught to wait for the right time but in today’s society the opportunity for knowledge is so great that it behooves each student to search out all opportunities. At the same time, the student has to be committed and dedicated. I’d rather see the student free to go after what they really want than be frustrated waiting.

The young kumu are criticized for their commerciality but the older people have to realize that there are exorbitant costs to be met. The expenses of 1983 are not the same as in the Forties and Fifties, and they have to be paid if the hālaus are to survive. It has been said that a culture dies if creativity stops. I am happy to see the young perpetuating the culture and traditions for in them is the future of Hawai‘i nei.

Keli‘i Tau‘ā has taught the hula on O‘ahu for the past five years and currently makes his home in Kihei, Maui.

I think the biggest stumbling block for the modern Hawaiian is the definition of who is and who is not Hawaiian. Many people still believe it is strictly a matter of race. Today being Hawaiian has more to do with a sincerity of feeling towards the fate of Hawai‘i than anything else.

In 1970 I was teaching Hawaiiana for the Department of Education at Waimanalo Intermediate School. Aunty Nona Beamer was serving as my consultant. I was required to learn hula for teaching purposes and so Aunty Nona invited me to train under her informally. I stayed with her for a year and in 1972 Aunty Mā‘iki Aiu publicly announced that she would be holding classes for hula teachers.

The hālau at that time was on Ke‘eaumoku Street and after some practices, I could hardly walk down the stairs of the second- floor studio. The “Hawaiian Renaissance” to coin a phrase of that time, was just starting to turn its wheels. Anything that was Hawaiian was a joy to learn.

I think the greatest thing that I came to recognize was that hula was not just motions but Hawaiian life, language, and folklore. That was the greatest joy, being in a place where I was learning not only the dance but something about myself in relationship to the past Hawaiian culture. What was there, and what it could be in the future.

More answers came from another kumu named Kau‘i Zuttermeister. I started studying intensively in 1973 with style and a feeling that I still possess today and transfer the stylings of Aunty Kau‘i to others. I started to teach in 1975. Two of my former classmates in Aunty Mā‘iki’s hālau, Robert Cazimero, and John Topolinski were really getting into men’s hula and it was exciting to me. There had been men’s hula when we were learning but there weren’t hālaus as we understand it today. They set the pace and helped to establish respectability for men to dance.

My approach was to show that hula was physical and demanding and required dedication and learning. That’s how in 1978 I ended up with a hālau of fifty- five men, half of them college or professional football players. My work has centered on kahiko because ‘auwana, as the word indicates, can be created by anyone, anytime, anywhere. My definition of hula kahiko is that of Edith Kanakaʻole’s. It would have to be movements passed down from generation to generation.

In the old days we were taught to wait for the right time but in today’s society the opportunity for knowledge is so great that it behooves each student to search out all opportunities. At the same time, the student has to be committed and dedicated. I’d rather see the student free to go after what they really want than be frustrated waiting.

The young kumu are criticized for their commerciality but the older people have to realize that there are exorbitant costs to be met. The expenses of 1983 are not the same as in the Forties and Fifties, and they have to be paid if the hālaus are to survive. It has been said that a culture dies if creativity stops. I am happy to see the young perpetuating the culture and traditions for in them is the future of Hawai‘i nei.

Citation

“Keli‘i Tau‘ā,” Nā Kumu Hula Archive, accessed February 24, 2026, https://nakumuhula.org/archive/items/show/85.